The other day I was working with some students and, even though I was not teaching them anything related to this subject, the topic of religion appeared in our conversation. Like a translucent visitor appearing in the middle of the room, that subject dealing with the ultimate questions arrived, totally uninvited. First of all, it is generally weird that I am teaching students, considering the fact that I was a student myself a matter of months ago. But second of all, for some reason, when I was going through this same program I am now an instructor in, many instructors brought religion up as a casual topic of conversation, which I mentally noted as something I did not want to perpetuate. These conversations always made me uncomfortable—they seemed to consistently head in the direction of stereotypes and negative generalizations. The instructors seemed to always assume my opinion on the matter, as if a grad student is anti-religious by default or something. Of course, it is amusing and ironic that the precise inverse was true of my undergrad: I was constantly pushing back against all the people who assumed I was Christian just because I was going to a Lutheran college.

First of all, I really don't like it when anyone assumes my opinion on the matter… Or any such matter! It bothers me likewise when my political views are presumed to be agreeable with my interlocutor... It is even common to engage in political grumbling, complaining that "oh, did you hear about this crazy thing this political party did". I can often agree wholeheartedly with the initial anecdote (if not a straight-up fact that kicks off the conversation), I can admit that that thing that happened, it was, like, really crazy, bro. And the that’s-crazy-bro anecdotes’ craziness can be usually be acknowledged without presuming one’s political position. But it is usually the follow-up to these sorts of friendly conversational anecdotes that I take issue with. It's common to say a platitude, something like "well, that's just how X group of people are".

I feel like I am encountering conversations like this all the time. Here’s the structure I’ve noticed is common:

a factual statement → a that’s-crazy-bro anecdote →a taken-for-granted platitude

Here’s an example of the sort of conversation that takes this structure.

[fact] Have you heard that Trump appointed Matt Gaetz to Attorney General?

↓

[anecdote] Isn’t it crazy that a convicted pedophile is being elected to the head of the DOJ?!

↓

[platitude] Well, that’s just how conservatives are. They love defending pedophiles. It’s probably because so many of them are.

This is an extreme example, but not an unrealistic one: if I were a conservative, admitting it now would mean I would make myself out as a defender of pedophilia. Yet I get on board with the facts and I can share the perspective on the anecdote. My objection is to the next action: to assume a far more fundamental perspective.

On the political front, conversations with people within my field tends to presume some level of on-boardness with the Democratic party. The conversations tend to focus on how much the Republicans suck, and then I am often presumed to agree with the sentiment that all conservatives are stupid, manipulative, greedy, ignorant, etc. etc. Now, it is often not the case that I actually disagree with what they are saying. I, in fact, think the current state of the GOP is a blemish on our nation's history, like so many others. But I have my own, particular reasons for thinking that. And just because I think that, does not mean I like the Democratic party in the slightest—I have always been an independent voter. And even though I am not conservative, I think there are plenty of strains of conservative thought which I think are actually valuable to society… but now discussing something like Alexis de Tocqueville or Jonathan Haidt will probably be off the table due to the establishment of a random conversational boundary I was too polite to object to. It bothers me that a common conversational mode has become to complain about something and then to move to some sort of platitude that the other party is supposed to inherently find agreeable. The conversations rarely have room for dialogue, exploration, or even questions. And when it comes to conversations around religion, I think this structure for a conversation is incredibly problematic. This is why "religion and politics" has been traditionally banned as topics of conversation at family dinners and such.1 We can easily imagine the equivalent conversation happening on religious terms. The topics are so deep and vast that trying to discuss them in such a setting will end up making everyone's views into crass imitations of their true views.

I call this sort of conversational subject "taken-for-grantedness". This is a term I am borrowing from a research paper by Anne-Marie Simon-Vandenbergen, Peter R. R. White and Karin Aijmer, called “Presupposition and ‘taking-for-granted’ in mass communicated political argument” which argues that taken-for-grantedness has become a predominant mode for persuasion. It is when one party in a conversation states an opinion, presenting it in a way that presumes their interlocutor concurs with it. Due to the nature of friendly conversation, the sort of material of the taken-for-grantedness (sticky, opinion-generating topics like religion and politics) will not likely result in the other party rejecting the presumption, not because they agree or disagree, but simply because it is the polite thing to do. In the aforementioned research paper, they use examples with terms like of course or it goes without saying. A really solid quotation/example they provide is:

It goes without saying that marriage is absolutely essential to a coherent and a good society….2

Something like this presupposes someone’s opinion. It puts the interlocutor into a position where they would have to push back if they disagree, in order to express their view on a matter which is known for having a multiplicity of views. An example I can personally give it when one of the instructors in my grad program said, “of course, I’m not religious, so…” And this rhetoric not only implies his own personal view, but assumes a type of norm in a realm where there is diversity. Similarly, at the Lutheran college I went to, instructors would commonly say similar statements, assuming the position of the student’s religious views to not only be identical to Christianity’s but the LCMS’s, even when such instructors knew, for instance, that they had a muslim student in their class. To me, these are examples of the same thing. And in my view, this means that the sort of topic that is best suited for dialogue becomes refitted into the kind of conversational tone we typically reserve for gossip. I see this as a great threat towards something like religious literacy.

Anyways, I vowed that I would avoid having this sort of approach to conversations with students. I did not want to assume that they had anti-religious views of any sorts, and if the topic ever came up, I wanted to approach it with curiosity and delicacy, and explicate a caveat that I will not delve too deeply into such a subject while I am operating the auspices of an "instructor" —because I'm not teaching them about my views on religion or politics. But when the topic came up yesterday, I found myself following that same old, despicable pattern. I shared some "that's crazy bro" anecdotes before not only saying a platitude-like statement, I invoked Nietzsche.

My God, why did I do this?

I don't particularly like Nietzsche, I don't think Nietzsche's philosophy should be lived out, and his views most often represent the diametric opposite of the sorts of views I hold. It was strange because the way I talked about religion was a taken-for-granted, but I was presuming a concurrence which even I did not concur with! And because we're still in the context of polite conversation, no real exploration or dialogue occurs. The cynicism lingers and whirrs in the room. I think this is particularly prone to happen in the context of discussing religion, because polite conversation is more or less synonymous with secular conversation. So while quoting the Quran, for instance, in the middle of a conversation might seem impolite and a bit obtuse, quoting Nietzsche isn't, really. The conversational default is often restricted to softball materialism and secular humanism.

To be fair, though, I did reference a pretty damn good passage of Nietzsche. In 1888, Nietzsche began conceptualizing a fascinating critique of Christianity, which I think is worth engaging with. Nietzsche comes to see Christianity as a form of affective nihilism, as a negation of life. Although Christians claim they are the furthest thing from nihilists, Nietzsche insists that positing a separate world where the meaning to existence can be found (i.e. afterlife) renders Christianity a negation of life.3 I think this is a very good critique, and engaging with it as a Christian would likely make you a better Christian. It's especially pertinent in the context of climate change, where a certain kind of religious conservative, instead of denying its existence, simply waves its consequences away because of the promise of an afterlife.4 In my view, this is nihilism indeed. And there are very good ways to counter such views which can be robustly based in theology.

The thing that bothered me, though, is that I was for some reason more willing to bring up a nuanced Nietzschean critique of religious thought than say anything positive about it, or to simply move past it... What does this mean?

How can it be true that I have spent so much of my life trying to learn about religion and to be respectful to religious beliefs of all sorts, and yet hesitate to express any of these sorts of sentiments in casual conversation?

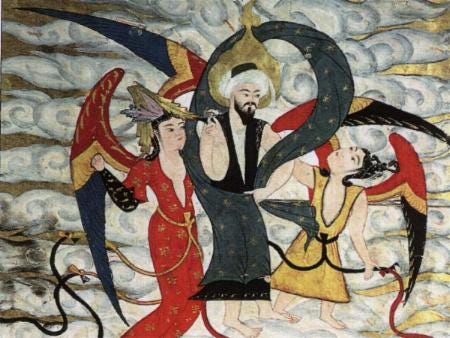

I really do think it is because our culture is so cynical. This is a simplistic diagnosis, but I think the cynicism in regards to relgion runs so deep in American culture that it is even a major aspect of religiosity. I mean, it's not like I haven't been in similar situations where the dynamics were flipped. And I insist, furthermore, that the larger problem than simple negativity is a wide-spread inclination towards religious illiteracy. Even when someone has respect towards a religion or even converts to it, I often see little effort made to understand it, much less for religion as a global phenomena. I've met a Jew who didn't know the story of Noah's ark and I have met a Christian who didn't know who Paul was. Not to mention the sort of person who love edgy statements like "if Jesus came back I would kill him again", but demand that Muslims be treated with respect... Do they not know that Muslims revere Jesus as Isa, as the penultimate prophet of God?5 It’s ironic that its become a popular liberal position to simultaneosly take the side of various Muslim causes and also think that religious people are stupid. Maybe they foolishly think that Muslim immigrants will happily abandon their rich religious tradition for stale grocery store secularism or maybe they think all paths reach their end at a very European idea of metaphysics. Everywhere I go, I meet people who not only reject religions but reject any opportunity to learn about them. Or, at least, they talk about religion as if that were the case. And, apparently, I am capable of doing this too.

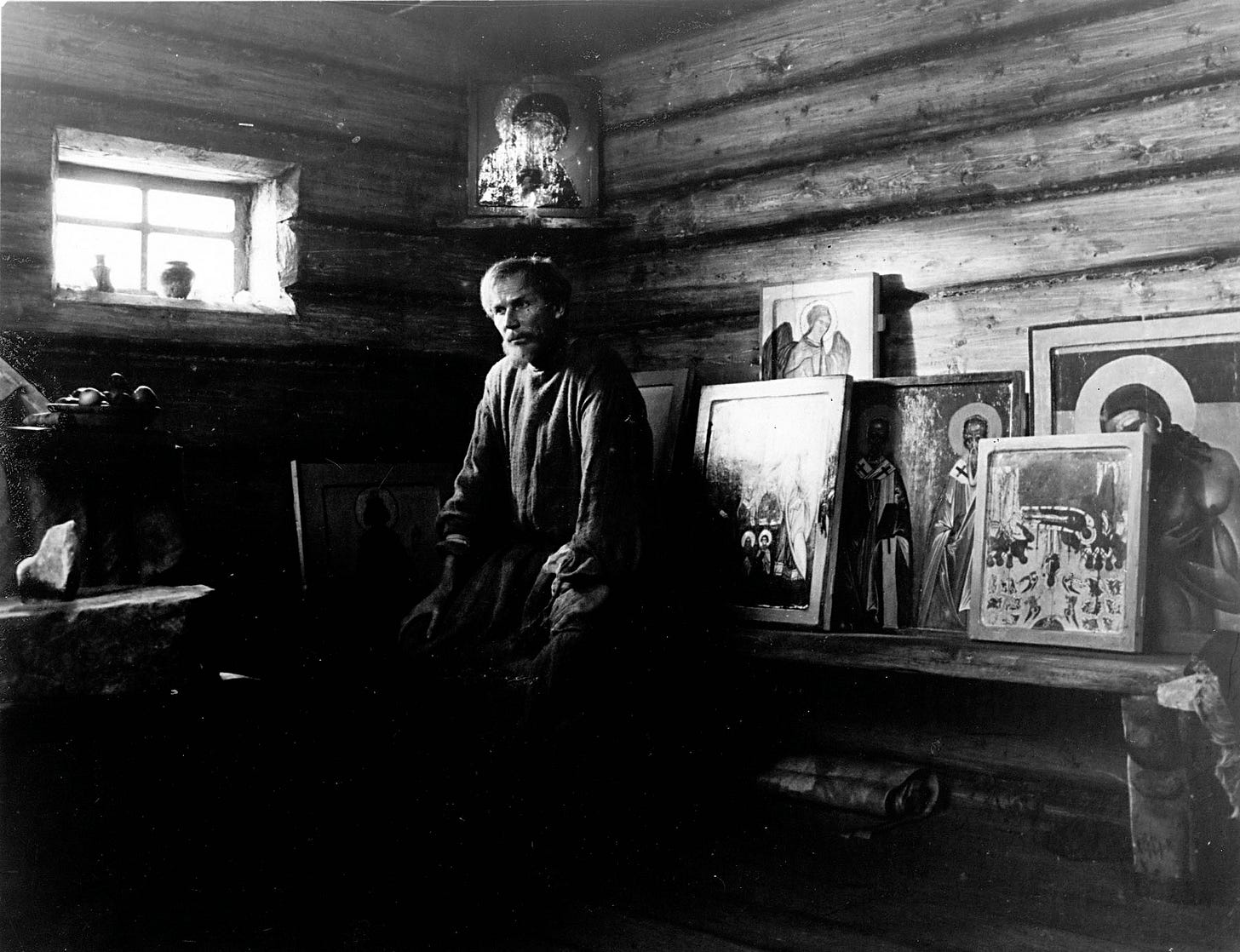

I’m surprised, even, at how many of my fellow cinephiles assume filmmakers are atheist by default. Tarkovsky is often considered one of the world’s great masters of cinema and he is easily my personal favorite artist of all time. But while many of my film-addicted friends have seen some Tarkovsky, they are typically surprised when I tell them Andrei Tarkovsky was Eastern Orthodox. And even more often, they ask, “what is that?”

I want to move in the other direction, to advocate for a very simple and humane, yet deeply unpopular, idea: religious literacy. What I mean by this, is to not only have the willingness to learn about other religions than your own, but to posses a nuanced idea of religion, to refuse to flatten the concept of religion into a stereotype which you can bludgeon strawmen with. One of my favorite videos by Dr. Andrew Mark Henry provides a succinct and profound introduction to the concept of religious literacy. He presents three fundamental concepts around religious literacy that can help guide one towards an open and curious attitude towards any religion. These three concepts are:

(1) Religions are internally diverse as opposed to uniform

(2) Religions evolve and change over time as opposed to being ahistorical and static

(3) Religious influences are embedded in all dimensions of culture as opposed to functioning in the 'private' sphere of social life6

These principles have stuck in my head ever since I first watched this video, especially the idea that "religions are internally diverse". This runs contrary towards popular understandings of religion, and it even runs contrary to the sort of depiction of religion many people get in their World Religions class in high school. If they ever receive such a class, that is. I think applying this sort of principle to our conversations about religion encourages an open-mindedness rather than taken-for-grantedness.

When I find myself in a conversation about religion in the sort of context where my interlocutor and I are sharing a cup of coffee (or maybe a swig of whiskey), it is a lot easier for me to extend open-mindedness and curiosity, to extend questions rather than presuppositions. But I want to have this attitude in the context of casual, polite conversation, too. I want to assume that I don't know the other person's spiritual journey, that even if they tell me that they are Catholic, that I can't automatically lump my assumptions and past experiences of Catholicism onto my perception of them. Just because you are Catholic does not mean that I know what being Catholic means to you. Just because you are atheist does not mean that I know what being atheist means to you.

The Religious Communicators Council is an organization which has made religious literacy their priority as an institution. I like the way they lay out the problem, as in the potential consequences of religious illiteracy:

"As communicators of faiths, we know what results when the media and the general public are unable to grasp cultural and religious nuances to the current events that arise in our world today"

And the way, they lay out the solution, the definition of religious literacy:

"1. A basic understanding of the history, central texts (where applicable), beliefs, practices and contemporary manifestations of several of the world’s religious traditions as they arose out of and continue to be shaped by particular social, historical and cultural contexts;

2. The ability to discern and explore the religious dimensions of political, social and cultural expressions across time and place"

This sort of knowledge is invaluable in today's world. We can find a helpful example when we see the way that conflicts in the Middle East are discussed. In the case of the Israel-Hamas war and the genocide perpetuated by Israeli State (which has caused the death of 43,391 Palestinians as of November 2024), we hear so many political explanations of why the conflict is happening, but rarely do we probe the true nature fundamental religious divides in the region, perhaps because they seem too obvious to state. But it is not as simple as we think. There is not just division between Muslims and and followers of Judaism, but also the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christians in the area, and the Bahai, and the Druze! (Have you heard of the Druze religion? Did you know that it grew out of Islam, that its followers believe in reincarnation, that many fought on the side of Israel but that their communities have nonetheless been bombed during the current conflict?) We cannot understand what this conflict means and what this land means to people if we do not understand their religions. Furthermore, we cannot fully understand the U.S. and Germany's continual support of Israel unless we understand the relationships as motivated, on some level, by religious prejudices and beliefs. Like so much of human history, your understanding will be incomplete until you take peoples' religious convictions seriously. How can one even make sense of the fact, much less understand its far-ranging implications, that Trump became the first sitting president of the U.S. who prayed at the Western Wall without some level of religious literacy? Understanding economics and politics will never be enough to understand the world… Religious beliefs are always lying beneath the surface of human life.

Personally, my life has been deeply enriched by attempting to become more religiously literate. Armed with the assumption that every religion is internally diverse, I can approach any religious subject with curiosity and assume that there will always be more to learn. It can frustrate me to see those who have antipathy to religion by default, but it also frustrates me to see people associating with religions without any sincere attempt to understand them and their corresponding histories.

In the writing of this little piece, I was mainly aiming to vent frustrations with... Myself. The fact that I willingly concede to the conversational default of taken-for-grantedness presumption,,,,, this bothers me. Despite all my efforts in the other direction, it still remains the path of least resistance in conversation. I think part of the issue is that I am actually too eager to offer a counternarrative that when there is no obvious opportunity to offer such a narrative, I end up reinforcing the same old anti-Religious story I was trying to avoid. Offering, say, a positive description of the Coptic Orthodox tradition or the Catholic Workers' Movement is the exact sort of thing I would like to do in casual conversations about religion. (Do you know about Dorothy Day's social work? Have you read Thich Nhat Hanh's take on Jesus' compatibility with Buddhist doctrine? Did you know that Christian Universalism is still a mainstream theologoumenon outside the West?) I'm absolutely chomping at the bit to talk about this nerdy, quirky religious stuff, but I know it's not the sort of thing that can slip easily into casual conversations. I often go the route of making my fascination with religion clear, by talking about the history, for example, of Mormonism or the legacy of the Millerite movement, but I think people assume, by default, that I want to make fun of the Mormons, the Jehovah's Witnesses, and so on.7 Not at all. I am legitimately fascinated by them, the same way I am with anything else I'm interested in.

But there is another way, and I would do well to remember it more often. Simply ask questions. Don't be afraid to probe people's assumptions, in a kind and friendly way. Try to not let anything in the conversation be taken for granted. Taking things for granted is not how we construct a stable middle ground at all, it's how we generate resentment and gossip. The only things I want to take for granted in any conversation is that every human deserves to be treated with respect, not in spite of their beliefs, but in relation to them… with an acknowledgment that their beliefs are part of them and that I often don’t even know enough by myself to assume what my perspective will be. Why wouldn’t I treat them the same way?

yes, this is my Thanksgiving post.

Simon-Vandenbergen, Anne-Marie, White, Peter R. R., and Aijmer, Karin. “Presupposition and ‘taking-for-granted’ in mass communicated political argument: An illustration from British, Flemish and Swedish political colloquy”. 42

This is somewhere in The Will to Power

Not all religious people, not all conservatives, but a certain flavor of religious conservatives.

This is not a strawman, I promise

Religion for Breakfast, “3 Things Everyone Should Know About Religion”.

if you’re curious about my interest in the Seond Great Awakening, you can read my essay, “on the great disappointment”

It is clear to me that you and I and many of our friends were raised in a very specific way that ended up with most of us having a desire to have this sort of nuance in all the things we approach learning and discussing. Some combination of where, when, and who during our childhood led us to this curious and nuanced approach. I have found myself shocked when a person who I thought taught me critical thinking, nuance, and empathy is suddenly lacking those in some parts of their life. I have a friend who will take so many nuanced stances on all sorts of subject matters except for conservatives. Anytime they mention a conservative it's with extreme hatred—with stereotyped assumptions and no nuance. It breaks my heart every time.

We are "orthodox rebels" in some sense. We want to know, understand, explain, and empathize with all perspectives, but not from a nihilistic, destructive way. We want to get to a truth that is devoid of dogma and bias, and understand the reasons for why people make the choices they do.

This "taken-for-grantedness" is a real problem. I've similarly experienced it in polite discussions of religion and politics. Your mentions of undergrad and grad school being opposites in religious assumption is something I also have felt. Bizarrely, it was between my two undergrad universities which were both religiously affiliated. Even within the same overall religion of Christianity, I am shocked to find these sorts of presumptions and Christianity-illiteracy. I was once in a Bible Study where the majority (including our leader) was willing to see Mormons over Catholics as "true Christians" even when there was a Catholic in the room. At another Bible Study, a woman who goes to Catholic Mass everyday was raging on the practice of praying to saints, and it landed on the shoulders of me—a Lutheran—to try to defend and explain the nuance of the practice. Even within the LCMS, the people who assume your specific stance on things are quite infuriating.

But, I would say the biggest place I have struggled with "taken-for-grantedness" is in grad school with relation to the material I am learning. The number of times that a proof has been called trivial or obvious is unacceptable—even when I can see the mathematics behind it, it's unfair to my fellow students. I have a professor who rarely, if ever, puts a conclusion on the proofs he covers in class. As if a diagram and a few statements whose connection is not always obvious is good enough.

When students ask me to solve problems on the board, I often won't do all the steps but only go over the tricky part of the setup. I then say things like, "you should be able to solve this from here. If not, go to office hours." Just two weeks ago I was preparing them for an example and said, "I hope you are able to do this, because, if you can't, you're probably going to fail this exam."

Assumptions are such a massive problem because they go unstated. In the world of mathematics, many proofs begin with a statement synonymous to "We assume X to be true, then by..." When we don't state our assumptions we make horrible mistakes—be the technical errors or simply poor communication. I sometimes wish regular conversations were more straightforward like that. I think I will try to be.

Totally agree on the conversation structure. That's very much my experience as well!