consider the pelican

the life of the frame rate & the death of the cinema

The concept of a frame rate is a strange one. Nowadays, its meaning has become increasingly fragmented and abstract. Running a video game at 120 fps is quite common, but in the cinema such a frame rate is nearly unimaginable. The very concept of the frame means something entirely different in the digital realm, as I have previously discussed in my A Primer on Video Game Preservation. But an understanding of frame rates is vital to a decent understanding of film history. In fact, the concept of the frame rate has become so vital to our modern cultural paradigm that the question "what frame rate is the human eye?" has become a common one. In this article I will briefly discuss why frame rates are the "essence" of cinema and why understanding this concept is of key importance to preservationists, historians, and enthusiasts alike.

0 fps

What would a frame rate of zero look like? This abstract question has a simple answer: the practice of chronophotography. While cinema's emergence is often associated with amusement arcades and sideshows, it has a similar progenitor in biological photography. As a way to study locomotion, Etienne-Jules Marey invented the process of chronophotgraphy. This was a photographic process in which you could capture movement all in the same frame, in other words, motion at 0 fps. This was the process which Muybridge used to capture the famous horse in motion-- often cited as the first film-- which was in direct response to correspondence with Marey. But a less iconic image than Muybridge's horse is that of Marey's pelican, which I find far more sublime.

I ask us to consider the pelican in order to remind us that frame rate was not something inherent to any technology, but rather, had to be discovered. This image of a pelican reminds us of the very reasoning used to come to this wonderful discovery of the frame rate. Put simply, the frame rate was born out of a desire to study motion. The images captured a form of movement through multiple exposures onto the same image. This practice gave way to the invention of chronophotographic gun, which was a tool for capturing movement which was designed to move in tandem with the subject. The desire to display images from these technologies led to the usage of projection and thus an embryonic form of cinema came about. As the images were played in sequence in order to emulate the motion they were capturing, qualities came out "between" the frames-- the illusion of motion itself.

It is important to remember that despite the fact that cinema cannot recreate images that perfectly resemble reality, it is somehow mysteriously able to activate the part of our mind which recognizes movement. If it were not able to, we would only see a sequence of still images. Cinema is more than the sum of its parts. This is why I call frame rate the essence of the cinema. The rate at which these images are presented to us determines the particularities of how the illusion of motion is perceived.

Of course, the illusion of motion is a complex and nuanced topic which I have discussed at length elsewhere in my “Do we really understand how moving images work?”

There is a common myth that the rate of 24 frames per second, the standard for the Hollywood film industry for much of its history, is the precise rate at which motion is perceived. But this is not true at all. The standard of 24 fps was formulated for entirely separate reasons. But to fully explain why this standard was chosen, let's first consider the frame rates used before such a standard was proposed.

16 fps

Most commonly, people assume that silent films are meant to be played faster than real time. The popularity of silent slapstick comedy, which was indeed often played fast, has made it the common reference point for popular conceptions of silent film. One imagines a jittery film with coppers chasing a burglar at 2x speed. Then, within the silent film loving community there has come about a sort of orthodoxy that silent films are not meant to be played at 24 fps but at 16 fps. This makes the films play out at a much slower pace and for a viewer who is used to watching the version of a silent film which is worn out, duplicated beyond belief, and sped up for no good reason— watching a silent film print in immaculate condition at 16 fps is a revelation. The actors' performances suddenly do not seem exaggerated but nuanced and sophisticated. It makes one realize that silent films were not just an incubatory era which had yet to achieve cinematic greatness, but that the silent film approach to filmmaking represents an entire, cohesive approach and tradition which was able to achieve things that the talkies were not, just as the inverse is true as well.

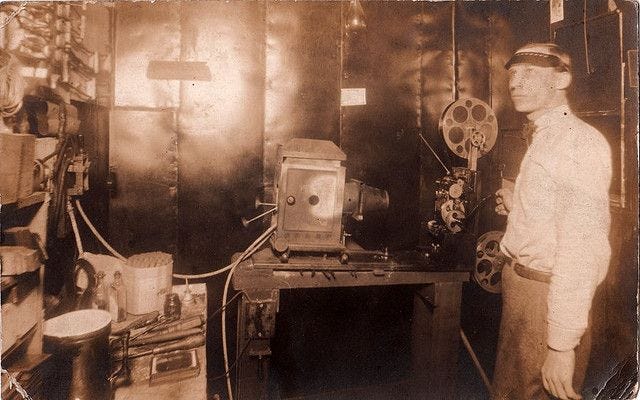

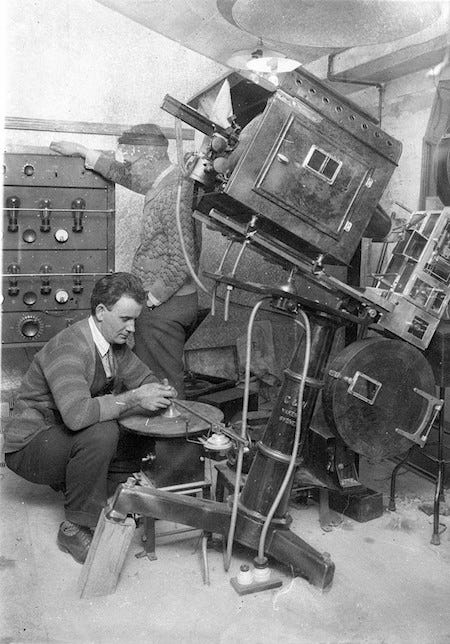

But this cinephilic orthodoxy of 16 fps is still not the whole truth and nothing but the truth. As James Card (founder of the Dryden Theatre) chronicles in his book Seductive Cinema, the honest truth is that playback speeds were constantly in flux. This is due to the simple fact that recording speeds were similarly in constant flux. To gain a more concrete understanding of what I'm saying here, consider the fact that film cameras used to be hand-cranked. While filmmakers and studios may have attempted some amount of consistency with which the various camera people would crank their cameras, the general rule was that the rate at which one captured, the speed of the film, was another form of expression. The faster one cranked, the more frames could be captured within a small frame of time and vice versa. For those unfamiliar with the state of frame rates today, this is similarly the reason why you want to capture footage you intend to apply slow-motion to at 60 fps. The more frames you have, the more you have available to slow down. Therefore there was a practice of capturing the climactic scenes of silent films at faster rates. The projectionists were correspondingly instructed to "shoot it out fast" when the time came! This made the scenes dynamic, exciting, and detailed. If a projectionist today just keeps the frame rate at a measly 16 fps during those scenes, the film will quite literally slow down.

But it was not a precise art. In general there was simply an expectation for the projectionist to react both to the film and the audience in order to set the speed. It may seem counterintuitive today, but projectionists really were something like musicians, and the performance of the film would change from night to night. The projectionists were literally understood as "enactors" of the films.

Furthermore, we get an even more complicated picture when we consider the musicians would accompany the films live, who would often work with the projectionists to find a general speed which worked for both of them. On top of that, movie theater managers often had their own preferences for speed which they would inform the projectionist of.

So what frame rate should a projectionist play a silent film at? I'm afraid there is no answer until the film has started playing. The silent film was a didactic medium in which playback was determined in reaction to the circumstances of the presentation, rather than a set standard.

24 fps

As said previously, there is a common misconception that 24 fps is used because it simply looks more "cinematic". This is what indie filmmaking guides and websites for filmmakers often claim. But the standard of 24 fps came about at a very particular moment in film history, for very particular reasons. It has to do with the invention of sound.

The coming about of sound in film involved two major products: the Movietone and Vitaphone systems. Vitaphone came about first and used a sound-on-disc system while Movietone was sound-on-film. Therefore it was the Vitaphone which set the standard.

As mentioned previously, the accompanist often was part of the process for selecting the frame rate used for a film presentation. The performance of the musicians would be in conjunction with the performance of the projector. It was not the "talking" of sound films that forced a 24 fps standard, rather, it was the replacement of the role of the accompaniment-- with Vitaphone came the quite literal "automating away" of the role of the musicians in the cinema.

The first sound film using this sound-on-disc technology prioritized the music. Audiences were not yet used to voices in the cinema, but music was to be expected. If a theater could simply play a record in sync with the film rather than hire an orchestra, piano, or organ accompaniment, they could save a lot of money. But the debut of this technology with 1926's Don Juan was a massive snooze fest. This resulted in the infamous "five-cornered agreement" where all the big studios agreed not to use Vitaphone-- except Fox.

Fox continued to experiment with the technology and the concept of the "sync score" began around this time. Many silent film restorations now simply use the post-1926 sync scores which were added by the studio for re-releases, rather than attempt to record a new score.

But then the voices found their way onto film-- experimenting with Movietone began and a recording of Charles Lindbergh makes audiences wonder what other famous voices sound like.

The "part-talkie" The Jazz Singer used Vitaphone and was released in 1927. This is not only miscredited as the first sound film but also as the film which set the standard of 24 fps. Such a standard already existed with the debut of Don Juan a year earlier.

The interesting thing is that because we stuck to this standard it has become the only frame rate we are accustomed to. Filming with frame rates slower or faster do not have the same amount of motion blur we have learned to enjoy, and projecting it at a different speed inevitably seems like an error. But 24 fps was a rather arbitrary standard. We could have chosen something else. But we have trained our eyes and our brains-- this why we think it looks "cinematic".

Without getting into it, TV broadcast set the standard not at 24 fps but at 23.976. This has to do with displays being optimized for the American electrical grid which uses 60 Hz. When films are presented at 24 fps on a display with a 60 Hz refresh rate, it causes "judder"-- you have surely noticed this effect in panning shots.

Many newer displays run at 120 Hz and display content at 60 fps to compensate. When the content was shot at 24 fps, it uses a process called frame interpolation to add extra frames. This effect, considering we have trained ourselves at 24 fps, is often despised by viewers and has been derided as the "soap opera effect".

The basic assumption that films should be displayed at 24 fps is quite an arbitrary one, however. And perhaps 24 fps is not the most cinematic after all-- perhaps a truly cinematic frame rate is one which is not consistent. This practice is true to presentation styles as they emerged in the cinema, and quite literally offers a quality which can only be had in the cinema.

A lack of knowledge in regards to how projection works may give one the impression that projection is a lackadaisical occupation-- that one simply presses "start" and gets to watch a film from the box. But film projection is not like this. It requires constant maintenance and flexibility throughout the screening. Film screenings were live performances. This is the essence of the cinema-- an essence we have, for the most part, lost. It is the standardized, mechanized, and digitized display of motion pictures which is uncinematic. I am not merely mourning the loss of true cinema, I am insisting that we don't even tend to grasp what it is that we have lost.

JPEG 2000

While I was working at a Regal cinema as a bartender, I told the manager I was interested in checking out the projectors and learning about that side of the work at the theater. One would expect such interest and offering of free labor to not go unnoticed. But I was consistently turned down. I found this curious.

One fateful summer day we had a theater full of children eager to watch Paws of Fury: The Legend of Hank (sure to be a classic for decades to come). But the movie was not playing any audio. It was silent. Parents were upset and came to the bar to complain. I subsequently told the managers. I observed, with curiosity, as the managers called someone else. Someone off site. Could it really be that there were no projectionists at all?

In order to fix the sound, the Regal manager had to call the national IT service which was able to remotely resolve the issue. I checked back in the theater. The sound was on. The children were laughing. And I was filled with an uncanny feeling. Do these children know that there is no one operating the movie? That digital commands from far-off computers dictated their experience of this artistic medium. Will these children go their entire lives without knowing what it is like to merely see a film projected by a human being?

No wonder megaplexes feel dead. No wonder you can feel the joy and laughter evacuating these communal spaces and becoming restricted to our own personal, tiny, artificial cinemas in our homes. Streaming services are not merely replacing cinemas-- cinemas are becoming streaming services with chairs attached. The last little shred of personal projectionist flourish left in these soulless husks are the DCP hard drives which come in the mail and require a manual "ingestion" into the theater’s servers. Otherwise it is entirely the domain of the machines-- quantized video data being translated into lights which can only be managed by an office worker in some miserable windowless room far away. It is automated until something goes wrong. Nobody is trusted to present anything. Features are no longer presentations, they are automated displays of videos. They are dead performances. The only human touch is that of the filmmakers-- but why should we stop there?

Let's have movies fully automated. Let’s make the screens needlessly bigger. Let's use large language models to presume what people want to see. Let's only use things they already recognize and remake every box office hit on a perfectly synchronized schedule. Let’s then wonder why nobody wants to go to the movies anymore.

Between the last two screenings you saw in the theater, it is quite likely that nobody even touched the machine that is displaying the films. You are paying to walk into a room and watch a computer. It just happens to be projecting light onto the wall rather than straight into your retinas.

Motion pictures have bled into our reality, our means of escapism are never escaping from the ongoing, cyclic cultural stew. There is no film playing in major theaters that a 12 year old couldn't find by typing "full movie online free" after the title in the Google search bar. No wonder theaters are closing all across the country. They have failed to distinguish themselves in any meaningful way from the broader cultural milieu. People want to see movies. They want to see feature-length, entertaining, thoughtful, meaningful, insightful pieces of audiovisual media just as they did in 1916. But nobody belongs in a dead place. In a non-place. First we replaced the musicians, then we replaced the projectionists, then we replaced the medium itself. We had changed every part of the cinema as if it were Theseus' ship-- and now it is functionally recognizable but has not retained any of its essence.

Consider the pelican. Films were created to study motion, not replicate it. They were never meant to capture reality-- but to display it in a beautiful arrangement. Young people will still fall in love with the films of Buster Keaton, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini. They are not any less intelligent or imaginative. But the art-hungry crowds of the 1910s, too, would have retained little enthusiasm for the medium of the motion picture if each theater were a mere mechanical contraption, with nobody around to talk about the film with before or after. Cinemas need to become places again before they can become cinemas again.

James Card once said his idea of hell would be to “have a projector and all the movies but nobody to watch them with”. Such is the plight of the modern theater. A comprehensive catalog at their fingertips, instantaneous and automated display methods… but no audiences to watch them. We have forgotten the essence of cinema. The projection booths are empty.

I can't help but feel the lack of a projectionist is only a small portion of what makes theaters feel like non-spaces. After all, people still happily eat bags of Doritos or loaves of Wonderbread despite no human hand being involved in their creation. Though, perhaps this junk food metaphor is an apt way of describing modern big cinema. There's both a desire for convenience and for bolder flavor without being new flavor.