the myth of the controlled environment

...and the terror of the minuscule

"Now I know what a rat in a maze feels like," says the protagonist in Phase IV. Such a line is usually referring to the master-plan of a genius villain. But here it is referring to the scheming of ants.

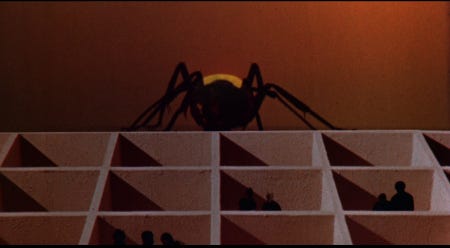

While watching this rather silly but beautifully constructed film, I was struck by the way the film engaged with contemporary notions of ecology and the usage of controlled environments in scientific institutions. It is a film about ants becoming sentient and climbing their way up the food chain. It is preposterous, fun, and has an impeccable aesthetic beauty. This is due largely to the fact that it is a film made by Saul Bass. In fact, it is the only film he ever directed. Even if you do not recognize his name you have surely seen his work. He is known for his pioneering and revolutionary work in the realm of title cards and posters. Many of cinema's most iconic opening animations (Vertigo, Psycho) came from his artistic sensibilities. Almost all of them were made in close collaboration with his wife, Elaine Bass. Their posters were so good that they are some of the only in film history that actually include a credit to the poster designer.

Phase IV was apparently a film thought up out of the blue. To quote Wikipedia,

The idea for Phase IV was apparently hatched over cocktails in 1971, when Peter Bart at Paramount had dinner with Raul Radin and asked him what's cooking. Radin responded an ant story, though he actually had nothing. Radin subsequently called Bass, who had a friend who worked with ants and they quickly agreed to work together.

So, they basically decided to make a movie about ants and worked their way out from there. They turned to the H.G. Wells short story "The Empire of the Ants" which was similar insofar as it depicted ants killing off a group of people in a single, isolated environment. Whereas Wells' story took place on a ship, Bass and Mayo's takes place in a remote research facility in the Arizona. Even though Arizona may seem like a pretty basic shooting location, the exterior shots were filmed in Kenya. I just point that out because it struck me as bizarre.

tiny intrusions

Phase IV's plot is pretty simple. We follow the two scientists at this research facility as they monitor the activity of ants. The thing, though, is that these ants have begun to be controlled by a mysterious cosmic force, causing them to be able to coordinate and plan in a way which is unprecedented. The research quickly falls to wayside as they launch a "war" against the ants, attempting to use their scientific machinery to destroy the bugs.

Key to the idea of this type of ecological research is the "controlled environment". The most dependable scientific results are known to be taken in controlled environments. It has evolved to be part of our modern conception of the "scientific method".

For much of my life, I took the idea of the controlled environment for granted. The idea that only the variables accounted for in a scientific experiment bear upon its results is somewhat commonsensical. However, I had my assumptions deeply questioned when I took a Philosophy of Science course. I was one of three students who had a background in philosophy rather than a background in the sciences. One of the philosophically-oriented students was a Psychology major. I remember my professor, Dr. Soper, always having fun poking fun at psychology for being a "soft science" due to the problems plaguing psychological experimentation and the unrepeatability of the results of many psychological experiments due to a lack of controlled environments.

But one day my professor flipped this dynamic on its head. If we consider, for a moment, that there are no environments can truly, completely control, then psychology is simply the field which is being the most honest about its limitations. He pointed out that, for instance, many science experiments do not take into account the minutiae of the weather outside of the testing facility which may have effects (i.e. static in the air) on the testing facility in ways which are easy to ignore.

That philosophy of science course demystified science and remystified reality for me. Science is a tool for obtaining near-certain knowledge about the world, rather than a totalizing vision which is being progressively revealed. And, strangely enough, Phase IV captures the imperfection of the controlled environment model and similarly depicts scientific pursuits as limited in the face of larger, psychedelic realities (it was released in the 1970s, after all). Due to the fact that the antagonists of the film are incredibly small, there are only very specific ways in which the film may play out its horror tropes. The film's genius is in depicting the undermining of a scientific, controlled environment.

Despite the fact that the research facility seems to be "entirely" separated from the outside world, there are always ways in and out of such places, as they must accommodate the coming and going of humans and the test subjects that are being introduced to said environment. Those tiny openings allow for something I will semi-seriously term the terror of the miniature. This is the idea that no matter how hard we may try to control all the variables, there are always deeper, smaller realities which intrude. To use an example from another famous sci-fi film about bugs: you may have an airtight door to your teleportation device, but the moment you open it— a fly may rush in.

taking account of all the factors

In the less obvious case of a physical bug intervening in a controlled environment, in the philosophy of science, the concept of the “nothing-else rider” stands in as the assumption that there are no other significant factors affecting a given situation. According to Nancy Cartwright (in The Artful Modeler), there are few if any cases where we can claim the nothing-else rider.

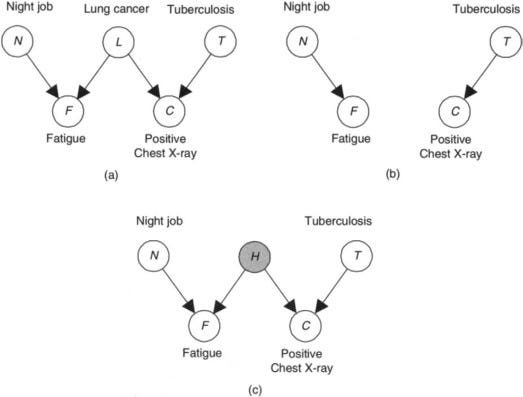

Consider Causal Markov conditions. Put in layman’s terms, such conditions inform probabilistic interpretations of causality. Just because you can give a case where A causes B does not mean you have accounted for all the variables that affect the outcome of B. To understand what caused B you must account for all of its “parent nodes”, but you can ultimately discard the nodes which are not directly its parent.

Such reasoning is used in medical diagnosis. This approach is compatible with efficiency. If I need to diagnose the condition in your kidney, I probably don’t need to be testing for diseases underneath your fingernails. But, sadly, God does not congratulate us when all the parent nodes have been found. The idea that all conditions have been accounted for is just that— an idea. Not an observable fact based on repeatable experimentation. The conditions under which facts are observed are modeled after our ideas.

The attempt to create a controlled environment is the attempt to limit all immeasurable influences on B. But most of these rules only fix what happens where only one specific domain can influence what occurs. Psychological experiments usually use non-representative subjects, such as college students. An experiment done on a mouse in a laboratory is done on a mouse in a laboratory. Mice don’t usually live in such places.

A prime example of the issues plaguing predictable observation in controlled environments is that of Gravity Probe B. In a satellite circling Earth’s orbit, Stanford attempted to prove Einsteinian theories of spacetime by measuring, with gyroscopes, the effect Earth’s gravitation has on its surrounding spacetime. After 20 years of completely controlling their testing environment, still one of four Stanford gyroscopes did not work according to plan. Only after 47 years and 750 million dollars did the experiment act in a predictable manner, returning meaningful results. Controlling an environment to get predictable results is costly and time-consuming, and while repeatability of experiments is the finest process of verification we can devise, it does not equate to epistemological certainty.

Then, there is the frustrating reality that nature simply keeps foiling our expectations. But this is, quite literally, natural. It is the way of the natural world. These are events which follow naturally once we go into the real world with our theories. The ultimately radical conclusion Nancy Cartwright comes to is that there are no rules nature follows. This does not mean, as one may immediately assume that the world is “random” or “chaotic”. There is no such thing as randomness, because every event implies a causal relationship. There are no uncaused events, therefore there is no randomness.

In Carl Hoefer’s words,

“The fundamental role (or better, roles) played by causation in scientific practice is undeniable; what Cartwright does, then, is reconfigure empiricism from the ground up based on this insight. In the reconfiguration process, many mainstays of the received view of science take a beating; especially [...] the fundamentality of laws of nature.” (Hoefer, Nancy Cartwright's Philosophy of Science.)

nature as system

What of those fields which aren't trying to test things in isolation, but are observing larger systems? Systems theory, cybernetics, and ecology represent a human urge to understand a part through the whole, rather than the whole through a part. This ecological turn in the biological sciences is the exact type of science Phase IV is depicting: in a certain sense, ecology sees nature itself as a controlled environment, or a system which maintains self-sustainability. This was the cultural milieu of the time. This builds off the assumption that human, sentient, thinking subjects can devise experiments and test the effects which emerge in ecosystems. But their mistake is thinking that nature will have predictable results in which all variables can be accounted for. The problem, in true sci-fi fashion, has to do with the fact that sentient thought can be unpredictable.

In the 1970s, the assumption that nature was a self-regulating system that always reaches a state of equilibrium was wide-spread. To quote ecologist Dr. Steward Pickett:

Ecologists really thought that they were dealing with a stable world. You didn’t question it. It was just like the air. You didn’t question it at all. The really remarkable thing is when people found out that this might have some chinks in it, that it might not be right… many ecologists were viscerally upset because it offended that very comfortable idea that nature was stable.

(Adam Curtis, All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace)

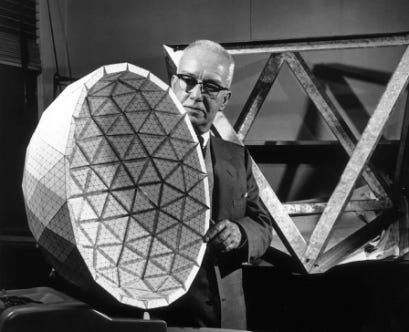

A profound symbol of the “stability” of nature were the geodesic spheres designed by Buckminster Fuller. These structures were meant to be literal demonstrations of how decentralized systems create structures which are stable and self-supporting. Communes such as Drop City used these geodesic designs to model their homes after. Fascinatingly, the laboratory in Phase IV looks eerily geodesic.

Ultimately, the conclusion the scientists come to in Phase IV is baffling. It is not nature which is the controlled environment, but their own experimental laboratory. The supposed test subjects become the scientists. The power dynamic is inverted as the ants "test" the two scientists to see which one is more intelligent and rational. The ending then imagines some freakish ant-human hybrid society of the future in an insane montage which the studio idiotically tried to cut. It can be viewed here.

The film’s conclusive turn towards considering nature as sentient and motivated may seem like a logical move for a sci-fi horror film. But it is also the path taken by many ecologists who have recognized a mystical quality in the emergent qualities of nature. I consider the issues with applying system theories to our ideas of nature in my forthcoming analysis of Octavia Butler’s Parable duology.

controlled environment as narrative impulse

You can see this narrative pattern elsewhere of the "controlled environment" as a broader trope even outside of science fiction. Think of Vertigo or 2001: A Space Odyssey. Additionally, there is a certain way in which religious narratives feature humans as test subjects in controlled environments. Think of the garden of Eden and the trials of Job. In Beau is Afraid, Ari Aster taps into the fear that life itself could be a type of controlled environment, manipulated by the archetype of an overbearing Jewish mother and a council which ultimately analyzes even your smallest, most excusable instances of sinfulness as worthy of condemnation. The urge to create controlled environments is just as universal as the urge to think we are in one.

Then there is the fascinating case of Synecdoche, New York in which a gigantic piece of art becomes a controlled environment emulating an entire city as well as the day-to-day life of the person creating the environment. The fascinating thing about this meta film is that it encounters much the same problem that modern physics has: one has to account for themselves in the environment as well.

I will not speak at length about this but due to the famous double-slit experiment, physicists have theorized the “observer effect”— the idea that simply by seeing reality, we change it. This poses a methodological and philosophical problem for the sciences. In order to observe phenomena as they exist in the world independent of observation we must remove the observer. But if we remove the observer we cannot observe the phenomena. The limits of what we can measure are synonymous with the limitations of the self… We cannot access anything outside of our own perceptions, thoughts, and abstracta. In Kantian terms, we cannot access things in-and-of-themselves.

In the case of Synecdoche, New York it becomes a problem of recursion. In the process of making an ultra-realistic theatrical production, the protagonist creates a “life size” replication of his city within a gigantic warehouse. The goal of the protagonist is to capture reality as it really exists, including the observer. Thus one must put themselves into the experiment as well as the putting of the self into the experiment into the experiment. So he hires actors to play himself in the play. And an actor to play the actor who is playing himself. The existence of the warehouse within the city implies that a totally accurate recreation of the city would include the warehouse in the recreation. The problem become infinitely recursive as a smaller replica is created within the replica in order to be an accurate model of reality, which by its very nature includes the experiment.

This is a very different attempt to create a "controlled environment" but it similarly ends up in a place where it encounters the terror of the minuscule— the minuscule in this case being the effect that even observing something can change it. And when we try to include experimentation within itself, we are forced deeper and deeper into the minutiae of the incompleteness of the experiment. The observer will always be a “hole” in the experiment— just as the optic nerve, which transmits the visual information from our eye, occupies space on our eye itself, blocking a region from obtaining input, and thus creates a quite literal “hole” in the center of our vision. Our brains fill the hole in. The hole in our perception of the world is always filled in or assumed. In the words of documentarian Theo Anthony, “at the exact point where the world meets the seeing of the world, we’re blind.” (All Light, Everywhere)

So the myth of the controlled environment is two-fold, as modern physics and ecology teaches us, that we can never control the output in its entirety if we can never totally control the inputs and that we can never remove ourselves from the equation. There is always a hole in the picture— and it is ourselves.

![Blu-ray Review] 'Phase IV' - Meh - Bloody Disgusting Blu-ray Review] 'Phase IV' - Meh - Bloody Disgusting](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bi_3!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0db3eb8c-abe1-4403-842e-ed8b9207d0d9_838x552.jpeg)