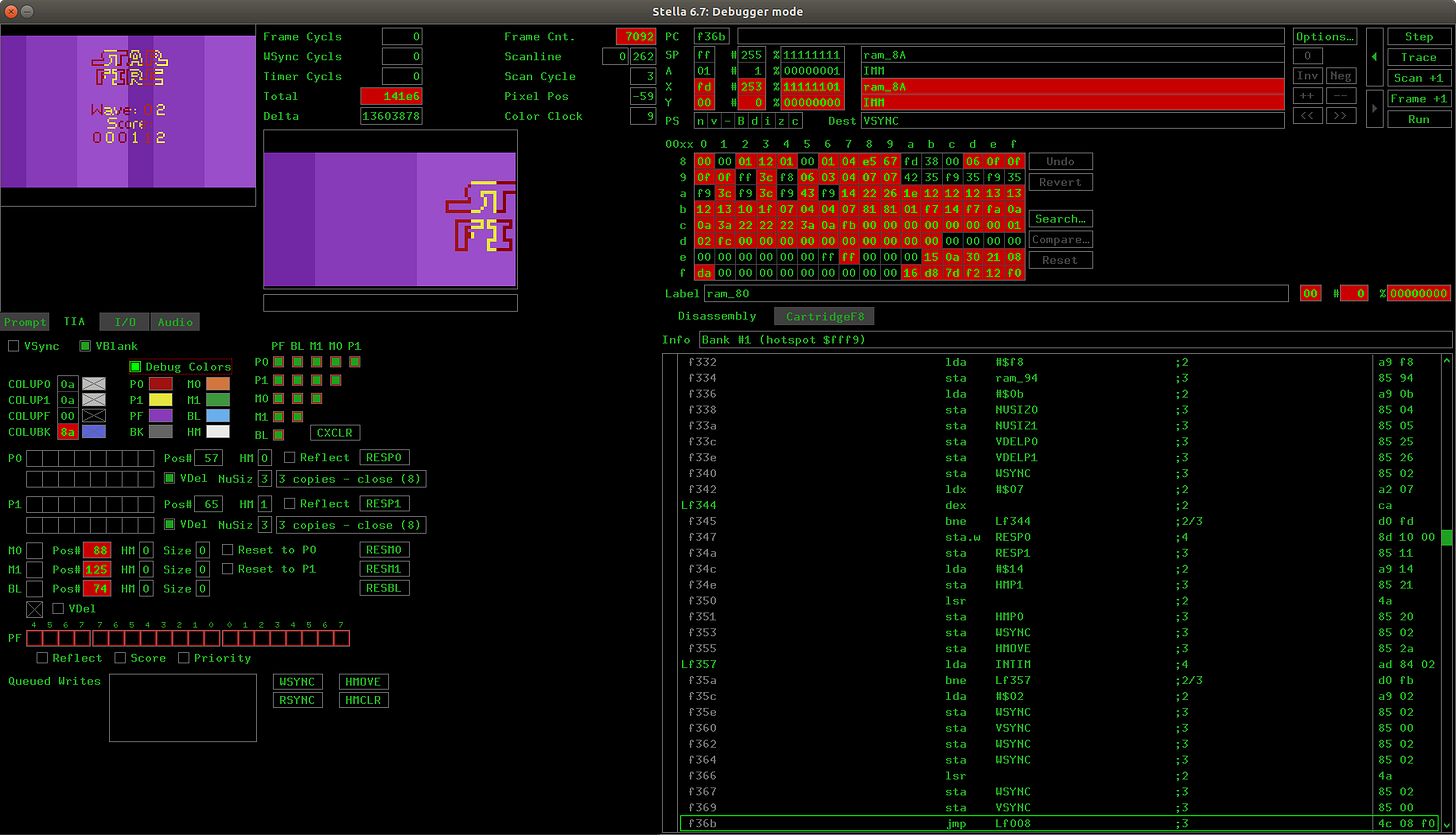

Emulation, on its most basic level, is a trick. Rather than making the original file of a game executable on a different operating system or console, emulation gives us a way to trick the program into thinking it is running on its native hardware. Emulation, quite literally entails creating digital equivalents to physical pieces of hardware. It allows for a more democratic access to classic games than any archive could offer. Many assume emulation is the way forward for the preservation of classic video games. What possible drawbacks could there be to this attitude?

Jon Ippolito in “Emulation” (an essay from Debugging Game History) argues that emulation has long been superior to the physical preservation of materials. He describes the moment the GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) community was ignorant of emulation in cynical terms, "while museum conservators and librarians were busily archiving digital files on CDs for the long term—with 'long term' meaning merely half a decade in the case of self-pressed CDs—their eight-year-old cousins were wielding a powerful technology that in theory could extend the life of bits into the indefinite future" (Ippolito 134). I am fond of Ippolito's characterization of pirates and librarians as "cousins", which I find agreeable with the views I have expressed earlier: in this case neither librarians nor pirates are doing the work of preservation. But the work they are doing may be the very real groundwork of preservation efforts to come.

I would like to return the cynicism upon Ippolito's own analysis: I find the notion that information uploaded to the internet has had its life extended into the "indefinite future" is faulty. It relies on a mythological notion of networks and cloud computing. It insists that grassroots, self-organizing networks of individuals will keep up the uploaded content out of their own self-interest. This is a lovely idea, but it is not a guarantee.

illusions of access

The future is always indefinite, not to mention unpredictable, but this is a compromise which is not necessary. These "bottom-up" efforts to preserve based off of the spirit of a "free information society" will always continue in one form or another. But there is no organizational demand to pay equal attention to all the materials they store nor is there payment for their work whereby these efforts have some modicum of a secure future. We need not place things in the "indefinite future", preservation standards demand us to think of concrete ways to ensure access for the centuries to come. But, as I will further argue in an upcoming post, the perception that piracy is preservation may discourage much needed funding for the real preservation work that has still not been done.

The self-justifying story of piracy as preservation is reinforced by the notion that preservation is access. I would like to offer an alternate vision: the problems with conceptualizing emulation as access (and therefore a form of preservation). Kindly note that access is not meant to refer to the ability of an average consumer to be able to play a game in any form at all, (in this regard, emulation is an unparalleled success) I am using the term access as shorthand to refer to the kind of access researchers are meant to have to archival, preserved copies of, say, a manuscript. Access offered to the masses is in no way being construed as a negative, in fact, I consider it of overwhelming important to maintain "research interest" by maintaining a healthy “preservation ecosystem"—for film, this means reparatory and arthouse theaters, museums, and archives; for electronic games this means retro arcades, emulation, museums… and the archives which have yet to come into existence.

As I will argue in this article, emulation is more than serviceable for maintaining such interest, and a healthy preservation ecosystem, but the need for accurate history demands rigorous archival practice— such standards should exclude emulation as much as possible.

Ippolito further considers the Art of Video Games exhibit by the Smithsonian as an exception to what should be the rule: a presentation of video games run on their original software and, in some cases, on their original hardware. He notes that this exhibit was pulled off because it is, after all, "the world's largest museum" (Debugging 134). He argues that even museums on this scale will be "hard-pressed" to preserve technology in its original state. I plead with Ippolito and the wider, cynical consensus that supersession has already doomed older technologies— wait!

Imagine if someone advocating for the preservation of film insisted, in the 1960s, that Nitrate film projectors would be too difficult and expensive to maintain, even for the George Eastman Museum, and we should therefore focus on transferring every copy to Acetate 16mm and cut our losses with the originals. This is, in fact, what most curators (such as Ernest Lindgren of the BFI) did with Nirate originals! If my museum took this approach, we would not have kept the master copies of Wizard of Oz or Gone With the Wind. Access to these films would be defined by the information loss caused by the displacement of the master copy from an original camera negative to a positive copy. Of course, every transfer on analog ensures a loss in information, so digital has an advantage in avoiding this dilemma. But it does not mean that a transfer is not still a transfer. Emulation gives the illusion of access.

the pixel art problem

What if, in the accessing of the content of an electronic game, one received a faulty, ahistorical perception of this piece of media? Let us call this, as the historians do, revisionism. We can find problems of revisionism occurring in access to classic video games rooted in emulation. A surface level issue can be found with the display process of accessing games via emulation.

The widespread usage of emulation, both on personal computers and on consoles, has led to the concept in popular culture of pixel art. Pixel art as an aesthetic ideal has become an iconic representation of "retro-ness" in classic games. Many independent games today imitate the style, and "pixel art" can be seen on numerous t-shirts, posters, and logos.

But this conceptualization of pixel art is based on emulation on modern TVs and monitors. Classic games as they were played in the 80s and early 90s never had the "pixel art" look due to the fact that they were always played on CRT monitors which have a distinctly "fuzzy" look. This makes the hard-edged squares which make up pixel art as an aesthetic a product of revisionism. We can find an interesting parallel in technicolor film.

The common perception of technicolor film nowadays is that it was ultra-saturated and eye-poppingly colorful. But consulting original technicolor prints shows one that the technicolor processing resulted in a visual that had an overall bias towards beige and orange. Restorations of major films done by film studios prefer to make the films look as people remember it looking as opposed to how they actually looked, this results in a reinforcement of the revisionist perception of audiovisual media. We can see a similar process occurring with the pixel art phenomenon.

I speak a bit more about this phenomenon in my post, “films that explode”.

ludic access

Consider the controller as a key towards access. In this section, I will consider the issues of playing games via emulators on your PC.

The particularities of interaction in a video game are of equivalent importance to the particularities of display in film. Playing a film at the correct frame rate and with the correct lens (scope or otherwise) is dependent upon any given venue which is displaying one of these works. In theoretical language, we can describe it as what gives the film a certain "texture".

What gives us the texture of a video game? It is not primarily the particularities of display, although these are of key importance, what is of most immediate importance is the controller itself. A world of emulation has flattened the relationship between controller and console/computer.

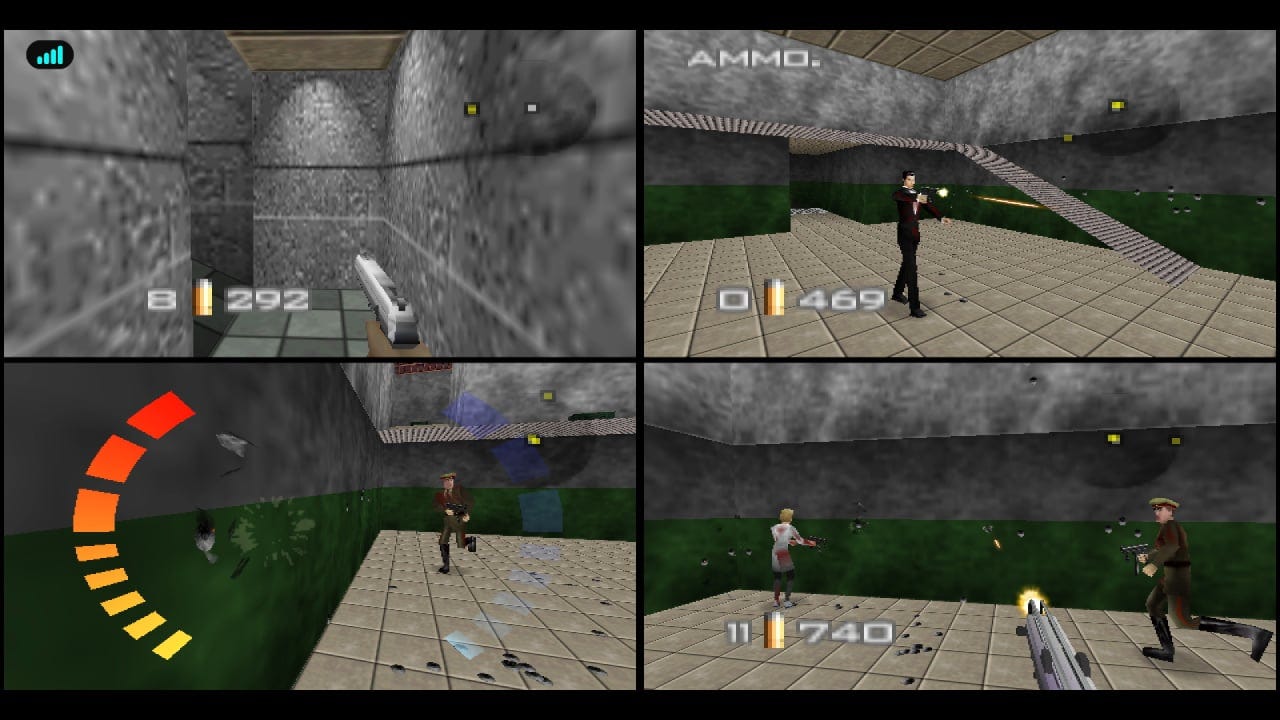

A modern generic controller is an agreeable blend of Sony and Microsoft innovations. It is seen as a "universal controller". With one of these controllers, an internet connection, and a willingness to defer to extralegal means, one can access an overwhelming amount of historic electronic game titles. But using one of this seemingly universal controllers will result in surprising amounts of revisionism.

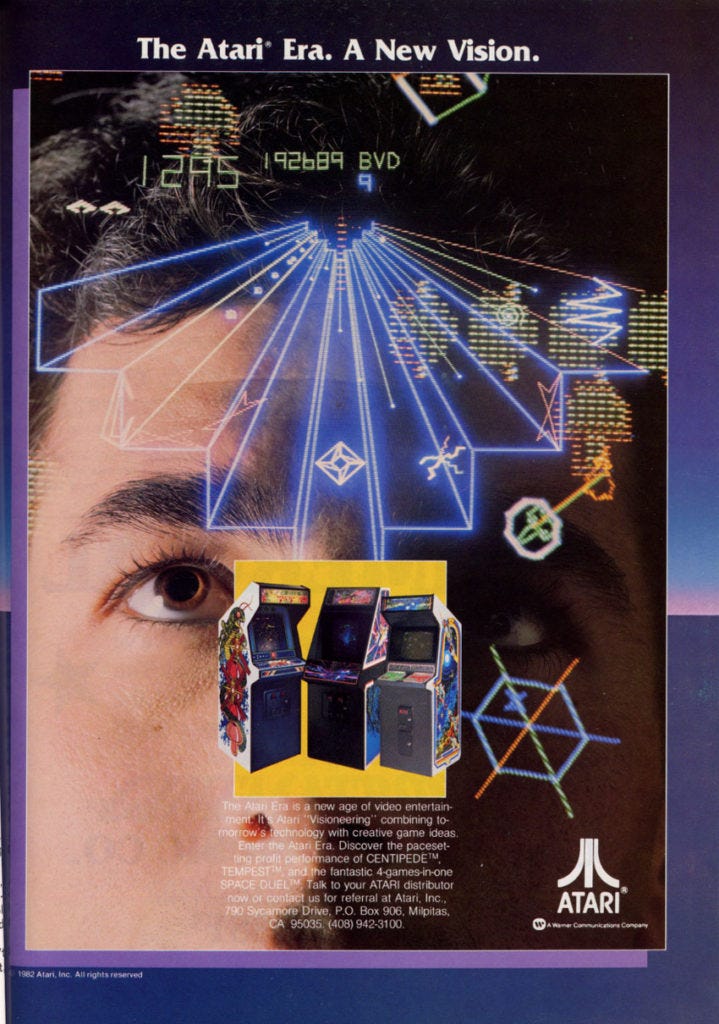

Take the simple case of an arcade cabinet game, say Tempest or Centipede. Both of these games have control panels which are are entirely non-equatable to a generic controller of today, nor with controls one can achieve with a keyboard and mouse. Centipede uses a trackball, while Tempest used something often referred to as a “paddle controller” due to its popular association with Pong-type games. How could one ever hope to “access” the experience of the game without the correct controller?

This is also a great example due to the fact that arcade fans are quite mindful of historical accuracy. There exists a whole industry of “replicade” in which classic arcade cabinets are recreated physically, though they use emulation. In the case of such games as Tempest, I would say playing it with the original controls is even more important than playing it with the original CRT monitor. If the controller is not preserved, then the particularities of the ludic experience will be lost. But I would also insist that this is just the most pressing issue for access, not the whole kit and caboodle.

infinite nesting dolls

John Ippolito argues that "daisy chaining" emulators offers a long term solution for preservation. Even if the the parent platform an emulator depends upon becomes obsolescent, one can run it in an emulation of this parent platform, and insists that this recursive strategy should work indefinitely. He cites Jeff Rothenberg's successful demonstration of having the "Windows-based emulator for the EDSAC (Electronic Display Storage Automatic Calculator), a forerunner of the modern computers built in 1949, inside the Windows 2005 emulator Virtual PC, which runs on Macintosh" (Debugging 137). Could such a Russian-nesting doll strategy work indefinitely? Perhaps it may. However, any potential problems with the emulation become embedded in such a form of access itself, and will likely compound.

This is the closest thing digital formats can get to an analog-to-digital process. If one watches a digital copy of a scanned film, it was created by quite literally taking digital photographs of the original film. The original film itself is often a copy of a copy, which were created via optical printers interpolating the film grains. Every copy gets grainier, just as certain qualities emerge in any duplication process, in what is popularly known as "feedback"— such issues similarly plague emulation. If we would like to avoid feedback and damage in film restorations, this is where the tool of restoration comes in handy. If we have various digital tools in order to restore a film to something like its original state on a different medium, how should we regard the principle of restoration in the realm of video game preservation? The technique of dynamic recompilation may offer a viable route towards video game restoration.

the aesthetic value of input delay

It is important to note that emulation is not a form of duplication. This has considerable advantages, particularly in the avoidance of feedback. One may copy a ROM infinitely without any feedback occurring. One may wonder what potential issues can emerge, however, when an emulator is put in a feedback loop. In other words, is there an equivalent to feedback which emerges when an emulator is running an emulator? If not, then Ippolito's infinite feedback is no problem. But the insurmountable issue with feedback is that of input delay. Due to the fact that emulation software behaves as if it were hardware, we theoretically do not need to worry much about variance between instances of running any given case. However, the process of "emulating" hardware will always, inherently, consume some amount of time. If one runs emulators within emulators, this input delay will inherently compound. While the issues may be nearly imperceptible in most cases, if we solely rely on emulation, as an Ippolito-esque approach may imply, then we will eventually encounter input delay so great that they will interfere with the ludic qualities of the game.

Ironically, the inverse may actually cause problems for access as well. Input delay can actually be reduced when running a game in an emulator due to superior video processing technology. But this can give us a faulty perception of the ludic qualities of a game. For instance, I had only played the Nintendo 64 classic, Goldeneye as an emulated ROM for many years. The emulator ran the game so smoothly to the point that it was super responsive to inputs and ran much like a modern first person shooter game. My experience of the game was rather dull and uninteresting. I simply did not understand why it was considered one of the best games for the system by many.

But when I finally played the game on its original hardware with the original controller, the input lag turned out to be an essential ludic quality. It was due to the lag that the game was challenging, surprising, and fun. This example shows that our previous discussion of the controller as key to access does not stop at the arrangement of buttons but has implications for the entire way that various pieces of hardware in a console interact with eachother. The input delay caused by using that particular controller on that particular console is entailed in accessing a historically accurate version of the game.

If I were a researcher playing the game on an emulated version, I would be ignorant of the unique type of play which occurs when input delay is a feature baked in due to hardware limitations.

seeing the fishlines

This is the equivalent of a film restoration removing the feedback inherent to duplication. Consider the case of restoring Time Bandits, in which Terry Gilliam found a restoration of the original negative actually revealed fish lines used for the film's special effects. Filmmakers at the time, such as Gilliam, had an awareness of what sort of visuals tended to disappear in the process of film duplication and filmed with those limitations in mind. In the case of special effects, this limitation could be used to their advantage:

There's always a tricky thing that happens with film because when you shoot on film, there's the negative and what people see in the cinema is a print— not a print of the negative— they see a print that's another generation between. So a lot of detail disappears and that's what I am showing the audience. Sometimes when you go 2K or HD, you suddenly pick up things you don't want to see [...] you're involved with people in the studios who don't understand the technical aspects of filmmaking.

'It was on the negative so it must have been what the director wanted'— no! We wanted what was on the print, not on the negative.

(Gilliam, interview)

So when the fishlines appeared in a 2k scan of the original negatives, it became necessary to digitally remove them in the restoration. In cases where limitations are overcome by restorations done with contemporary technology, deliberate imposition of those limitations becomes revisionism. But in our terminology, the resultant digital copy of Time Bandits is a restoration rather than a preservation of the original materials. Emulation seems to resemble restoration in film far more than preservation. However, we can push this concept even further.

If emulation, as it is traditionally understood, is not a route towards preservation, then what use could it have for GLAM institutions? I would like to argue that emulation and related techniques may offer a way to restore video games rather than preserve them. In this regard, recompilation as an approach to video game restoration may be the future. I intend to touch on that in a later post.

Emulation is not the opponent of preservation at all, but we should not convince ourselves that the two are synonymous.

sources

Debugging Game History

![CEMU] MK8 SplitScreen has WAY too many visual glitches | GBAtemp.net - The Independent Video Game Community CEMU] MK8 SplitScreen has WAY too many visual glitches | GBAtemp.net - The Independent Video Game Community](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!samM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5f56aed6-8a5e-4a4a-a360-89e8a750ecbc_1282x772.png)

I wonder about the nature of emulation of the limitations of hardware. Many archives do not have their collections fully accessible. Manuscripts are often too delicate to allow for normal or general perusal. Instead, they produce high quality scans which can be explored digitally in some manner. An archive with access to original hardware could create limitations in an emulator. We can emulate an appearance, to some extent, of a CRT. If our emulators are powerful enough, we can have them include the right amounts of delay and limit them so as to not restore their memory, but instead restore as close to actuality as possible. Consider a perfect "replicade" that, while running on newly constructed hardware, plays exactly the same as an original machine. An archive containing the original is required so that the arcade machine can be intricately studied and copied. Perhaps even multiple so that the emulation is not a copy of the singular machine but of the overall group of machines.

Also, I would like to propose a term that is some variation of "archade" or "archide" for ludic archives.