4. The Modern Creation Myth

The accumulation of all these elements which expand or alter the original Hebrew creation myth result in a significant development toward a new myth. Milton was not alone in this slow mythological development, although Paradise Lost can be considered an undeniable turning point; this paper only addressed a small portion of Milton’s contributions which also included the portrayal of the fruit of knowledge of good and evil as an apple as opposed to the traditional Jewish fig, the expansion of the Tree of Life mentioned in Genesis, and of course, the lives of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. All these changes resulted in a creation myth so altered it is inseparable from Western culture. The modern common notion of the creation myth can be said to be chiefly influenced by Milton.

Some cases show that ideas present in Paradise Lost have influenced theological doctrine. In fact, Paradise Lost can be seen as preceding the creation myth of the Westernized form of Christianity of Mormonism, as one Mormon scholar writes, “the poem corroborates some of the truths of the restored gospel” (Arnold). The implications of fictional literature encroaching on new religions is curious, and while it obviously cannot be known whether Joseph Smith was aware of Paradise Lost while he wrote/transcribed texts such as the Book of Moses, the cultural influence Milton must have had in the 1800s must not be underestimated. Forming a new religion in the vein of Christianity unsurprisingly involves drawing from folkloric beliefs surrounding the Christian canon, epitomized by Milton, and for Mormons, actualized in the “restored gospel”. Elements such as Satan’s rebellion due to jealousy of Jesus, the pre-creation angelic war, and even the hierarchy of the triune God are all affirmed in Mormon scripture. Similarly, Mormon cosmology can be described as a type of dualistic cosmology.

Beyond Mormonism, Milton has undoubtedly influenced the ways many Christians and the general population think of creation. Perhaps one of the easiest ways to trace Milton’s influence is his depiction of the forbidden fruit as an apple. The symbolism of the apple likely came into Milton’s narrative by way of Greek mythology; although it was the apple that was depicted as the fruit prior, Milton once again epitomized this image. Wherever the apple appears as the fruit in the Garden of Eden, whether in art or literature, it’s safe to say there is at least an inkling of Milton’s legacy. Similarly, the serpent being the literal snake, and the angelic war all point to the subconscious imprints of Paradise Lost in popular culture. But while Christians and the general populace may believe they understand the intentions of biblical scripture, do they understand the intentions of Milton, who has demonstrated such a great influence on our cultural understanding of the creation myth?

5. Miltonian Doctrines

Reading Paradise Lost as a literal development of the Genesis creation myth can lead to some curious theological implications. To fully understand the weight of these implications, distilling these ideas from the poem will result in some distinct “Miltonian Doctrines” (as they will henceforth be referred to within the scope of this paper), which seem to paint a portrait of creation far different from Hebrew or even other Christian accounts. Whether Milton sincerely believed any of these doctrines, or whether they existed before Paradise Lost, is irrelevant; Milton epitomized these doctrines in his epic poem, and some proved to be influential in the realm of Christian interpretation of Genesis. Some of Milton’s ideas may have directly influenced Christian orthodoxies, while others were, and continue to be, deemed heretical. The two key Miltonian doctrines which are essential in understanding Paradise Lost and Milton’s influence on Christian thought are intertwined with each other: dualism and hierarchy. Thus, Milton’s cosmology may be labelled a dualistic hierarchy.

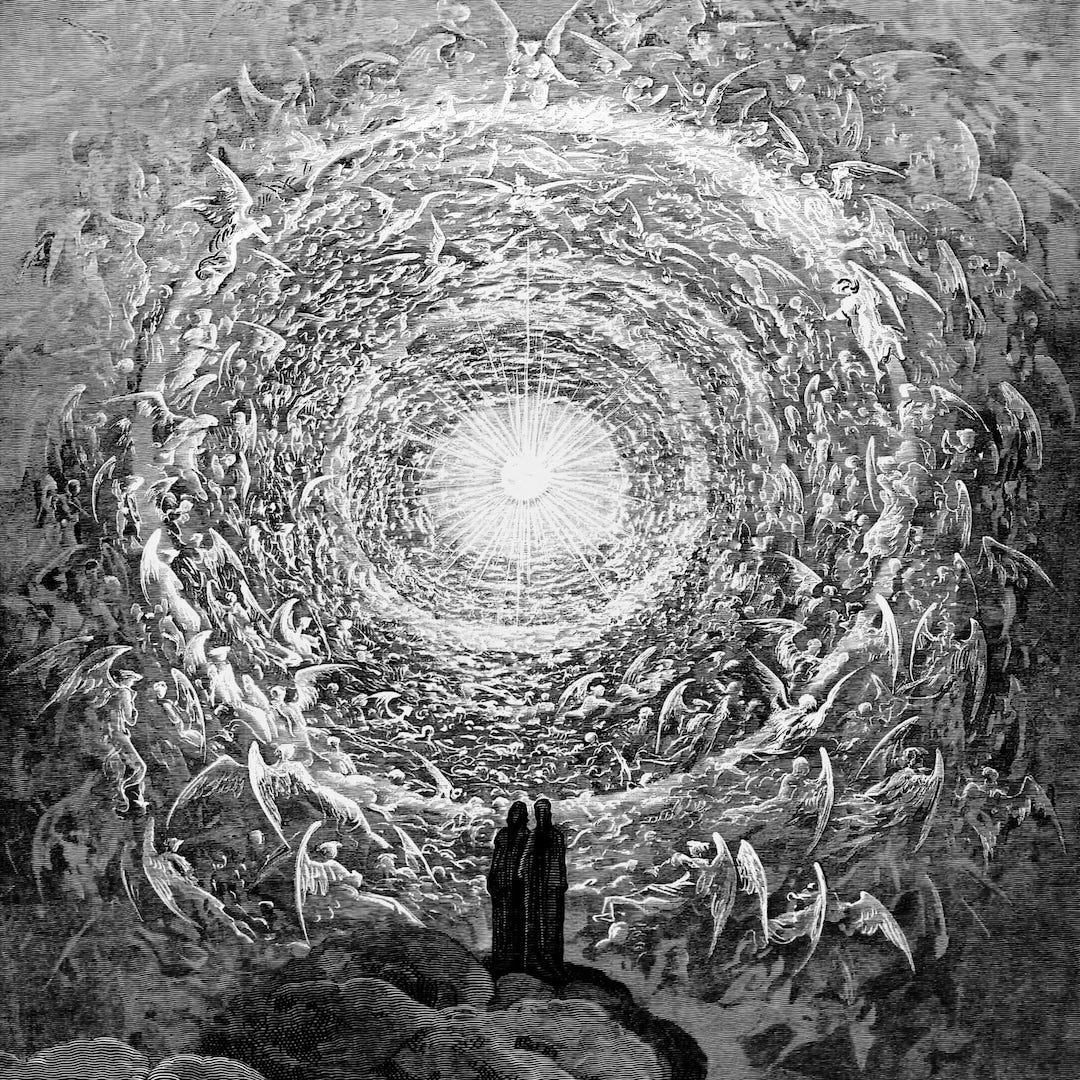

Milton’s depiction of the world is defined by his inclination towards a dualistic cosmology. Satan as depicted in Paradise Lost is the leader of a warring force which opposes God. Early on in heaven there is a clear separation between who is good and who is evil, “then all thy saints assembled, thou shalt judge/bad men and angels, they arraigned shall sink/beneath thy sentence; Hell, her numbers full,/thenceforth shall be for ever shut” (Milton, 61). The category of evil being applied is not one constituted of individual actions, but of the nature of a being.

The second Miltonian doctrine which is clearly represented in Paradise Lost is a distinct hierarchical ordering of the universe. Within his cosmology, there are hierarchical restrictions everywhere, even within the figure of God. As previously stated, God “begets” Jesus at a specific moment, and is represented as being subject to God the Father. In Milton’s view, there seems to be an implication of the Trinity containing separate entities, therefore three different gods, in which, “the Son and the Holy Spirit participate in the substantia of the Father” (Patrides, 429). This hierarchy is reflected in the rest of Milton’s world as God is above the angels which are above the demons, which are above the humans, which are above nature. Notably, demons are explicitly placed above humans, “godlike shapes and forms/ Excelling human, princely dignities,” (Milton, 12). This points towards the blend of dualism and hierarchy in which even good and evil forces have divine placement in Milton’s cosmology.

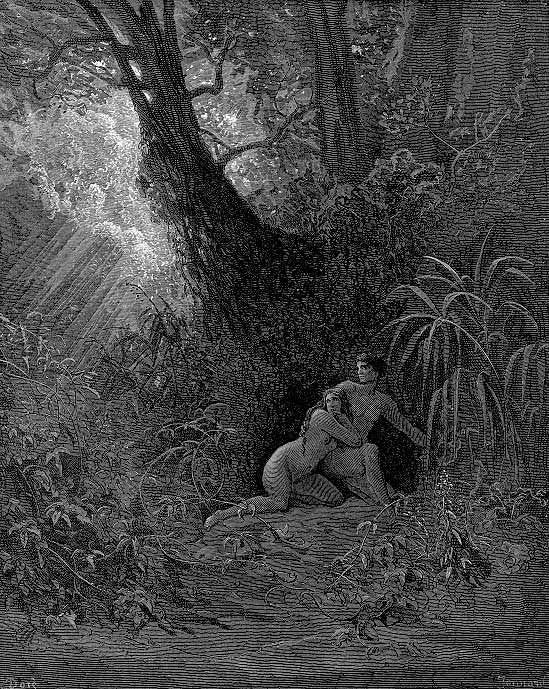

This hierarchy is similarly reflected between the relationship of Adam and Eve, where Adam is meant to “govern” over Eve,

And for thee, whose perfection far excelled

Hers in all real dignity: adorned

She was indeed, and lovely to attract

Thy love, not thy subjection, and her gifts

Were such as under government well seemed,

Unseemly to bear rule, which was thy part (Milton, 221).

Milton makes it clear that the genders are also part of a hierarchy, and links the governorship of Adam over Eve to that of man over nature. While Milton does depict Eve as autonomous, Eve is ultimately subject to Adam, much like the way Jesus is subject to the Father (Tanimoto, 85).

If this hierarchy is divine, then rebellion against it is demonic, as evinced by Satan in the narrative, who wants to be equal with God. Because Satan is “obsessed with equality” to God, and refuses to submit to Jesus, he is cast out of heaven (Bernhard, 36). Yet Satan can also not help creating his own form of hierarchy in Hell. The other major point of divine punishment in the poem is the Fall of Man, which is caused by Adam and Eve attempting to be equal to God by eating of the fruit. And so any attempt to rebel against the divine hierarchy is seen as evil. Milton’s view can be distilled as such: there are forces of pure good and pure evil; the forces of pure good maintain their position in the divine hierarchy, while the forces of pure evil attempt to rebel against it in pursuit of equality.

6. The Need for a Post-Miltonian Creation Narrative

If Milton has had such a powerful influence on the Christian and public imagination, what would it look like to strip the creation story of his influence? What if we were to view the creation story without a hint of dualism or divine hierarchy? What if we were to resist calling the serpent Satan, to not assume a pre-creation Angelic war in heaven, and to assume God’s presence at the beginning of the world to be less anthropomorphized than Milton’s depiction? What if we were to brush away extrabiblical influences from the Genesis creation story? I will attempt here to lay out some brief ideas for alternative readings of the creation story in Genesis.

Such an approach would likely distance the story from reading approaches which become all too familiar, that Eve is inherently subject to Adam’s governance, that evil somehow entered the Garden of Eden, and that God’s ultimate ideal for his creation is hierarchical. Without the vivid imagery often provided to us by Milton, the creation narrative in Genesis takes on a much more mysterious and abstract quality. Perhaps accepting the mysterious nature of this ancient prose, along with the embracement of its original cultural context will provide us with some surprising insights as to the story’s meaning.

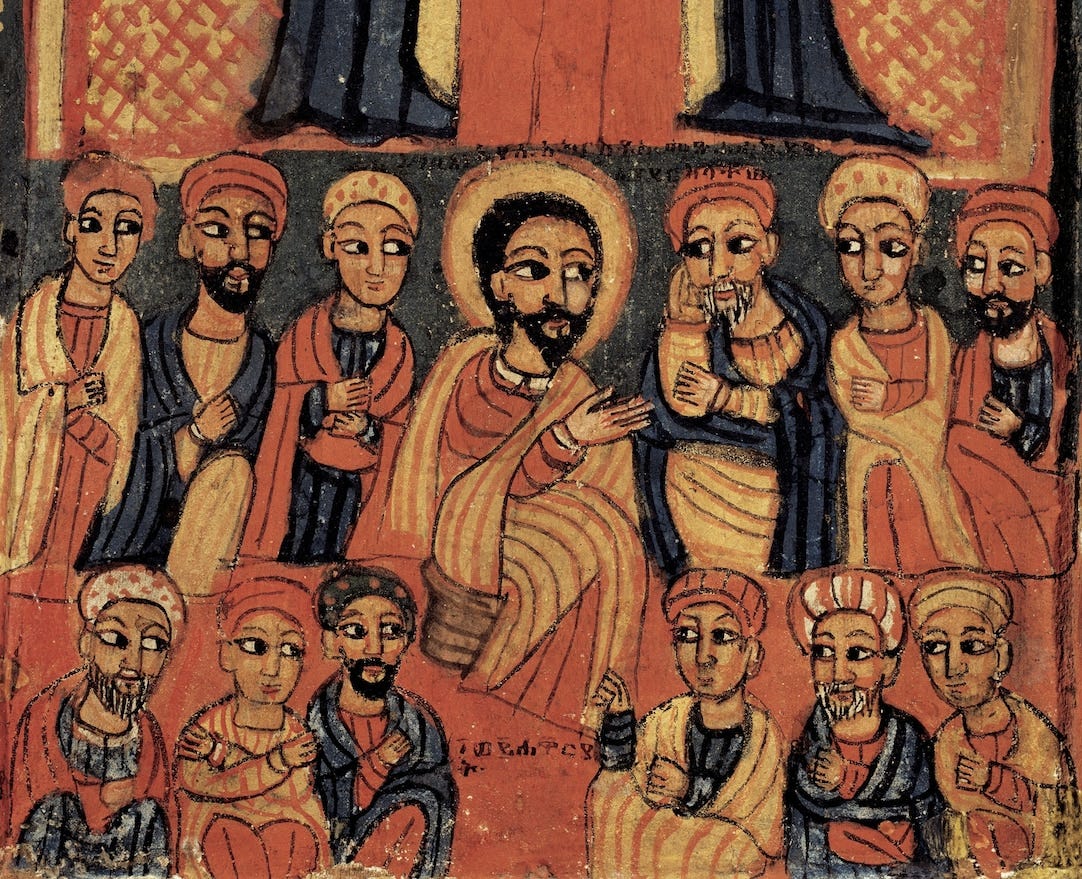

With Milton’s influence, we have learned to emphasize certain aspects of the story and deemphasize others, but if we consider such elements as God interacting with Adam and Eve, and “walking” in the garden, it seems as if God wants to be on an equal footing with his creation. In the alternate tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy, Jesus’ incarnation was bound to happen even if Adam and Eve did not sin, as the purpose of the incarnation is Jesus achieving an “equality of being”, desiring humans to draw closer to God through the process of theosis (Hudson, 138).

Similarly, a dualist cosmology is in no way inherent in the creation story. The serpent need not be representative of a cosmic force of evil, but can be read as the representation of the ability to sin and tempt others which lies in all creation (similar to the aforementioned concept of “Yetzer Hara”). If one is to take a more existentialist approach to the narrative, and assumes that humans are beings of free will (and that there are no warring cosmic forces of good and evil as in Milton, but rather using an approach to morality as defined by subjective relationship with God) then the act of eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, (an act which was only wrong because God designated it as such) can be seen as not gaining more knowledge but actually a reducing of knowledge to simplistic moral categories which are not divinely ordained. Perhaps the serpent was truly lying when he said the fruit will make Eve “like God”; after all, why should we trust the serpent? If so, then humanity's first sin is to choose to simplify morality, and to reject the notion that morality is defined in our relationship with God, and thus to reject the notion that “God is love”.

Milton, through his aspirations to write a definitive, Christian epic about creation, forged his own myth. He used influences from his own cultural context, yet this approach had unintended consequences. Although Milton sought after great literature, he perhaps got more than he bargained for in the long run, as many Christians may find his version of creation more familiar to them than the original. Milton has punctured the Christian subconscious, linking Revelation to Genesis, creating a cohesive Westernized narrative, one which assumes the presence of Jesus and Satan from the beginning of the story, and subsumes the original development of such a myth. In regards to Christians who believe in the Miltonian battle between God and forces of evil (and who speaks of “spiritual warfare” between demons and angels who battle on an equal playing field) it can be difficult to discern whether they are being more influenced by the Bible or by Milton. If we wish to see Genesis more accurately, we must move away from this extrabiblical influence of Milton’s, in pursuit of a more scriptural approach.

Works Cited

Arnold, Marilyn. “John Milton: An Inspired Man.” The New Era. Jan. 1976,

Accessed 25 Nov. 2020.

Bartelink, Gerard. Demons and the Devil in Ancient and Medieval Christianity.

Edited by Willemien Otten and Nienke Vos. Brill, 2011.

Bernhard, Katherine. Paradise Impaired: Duality in Paradise Lost. Florida Atlantic University.

Blake, William, and Michael Phillips. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Edinburgh, Michael Phillips, 2018.

Butler, Francelia. “THE HOLY SPIRIT AND ODORS IN PARADISE LOST.”

Milton Newsletter, vol. 3, no. 4, 1969, pp. 65–70. JSTOR, Accessed 20 Nov. 2020.

Cook, John Granger. The Interpretation of the Old Testament in Greco-Roman Paganism.

Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2004.

Collett, Jonathan H. “Milton's Use of Classical Mythology in ‘Paradise Lost.’”

PMLA, vol. 85, no. 1, 1970, pp. 88–96. JSTOR.

Crossley, Robert. “My Ever New Delight: The Pleasures of Paradise Lost.”

The Hudson Review, 2018. Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

Crossway Bibles. ESV Study Bible: English Standard Version. Wheaton, Ill.,

Crossway Bibles, 2016.

Day, John. From Creation to Babel Studies in Genesis 1-11. London [U.A.]

Bloomsbury Acad, 2013.

Davis, John D. Genesis and Semitic Tradition. Nabu Press, 2010.

Green, Jennifer. "A history of Satan; New Course at Ottawa's Carleton University

examines Western beliefs about and portrayals of the devil". The Gazette

(Montreal), October 2, 2010 Saturday. Accessed November 24, 2020.

Hudson, Nancy J. Becoming God : The Doctrine of Theosis in Nicholas of Cusa. Catholic

University Of America Press, 2007.

Jacobs, Louis. The Jewish Religion : A Companion. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Jonge, Marinus De and Johannes Tromp. The Life of Adam and Eve and Related Literature.

Sheffield Academic Press, 1997.

Mills, Watson E, and Roger Aubrey Bullard. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, Ga.,

Mercer University Press, 1992.

Milton, John, and John Leonard. Paradise Lost. London, Penguin Classics,

An Imprint Of Penguin Books, 2016.

Patrides, C. A. “Milton and Arianism.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 25, no. 3, 1964, pp.

423–429. JSTOR.

Peter, John Desmond. A Critique of Paradise Lost. Hamden, Conn. Archon Books, 1970.

Reed, Annette Yoshiko. Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity :

The Reception of Enochic Literature. Cambridge, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

Revard, Stella Purce. The War in Heaven : “Paradise Lost” and the Tradition of Satan’s

Rebellion. Cornell University Press, 1980.

Stokes, Ryan E. “Satan, Yhwh's Executioner.” Journal of Biblical Literature,

vol. 133, no. 2, 2014, pp. 251–270. JSTOR. Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

---“The Devil Made David Do It... or ‘Did’ He?

The Nature, Identity, and Literary Origins of the ‘Satan’ in 1 Chronicles 21:1.”

Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 128, no. 1, 2009, pp. 91–106. JSTOR,

Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

Tanimoto, Chikako. Milton’s Eve in Paradise Lost. Global30.

Varandyan, Emmanuel P. “Milton's Paradise Lost and Zoroaster's Zenda Vesta.” Comparative

Literature, vol. 13, no. 3, 1961, pp. 208–220. JSTOR.

you can keep reading my series on Paradise Lost here:

Pericope Adulterae

Note: I originally wrote this story in 2021. It was inspired by my obsessive studies of Milton. Pericope Adulterae “Neither will I condemn you; go and sin no more.” Anonymous I had first come across the poetical works of Johannes of Ibiza in 1943 in a book store in Rome. In this obscure little place in Via del Corso I found his

how Paradise Lost changed the world

Have you ever heard of Paradise Lost? The answer to that question might heavily depend on what generation you were born in. When my parents were in school, it was still standard practice to make American High Schoolers read Paradise Lost. The book used to be so widely read and referenced that many phrases from it have become as ubiquitous as Shakespeare…