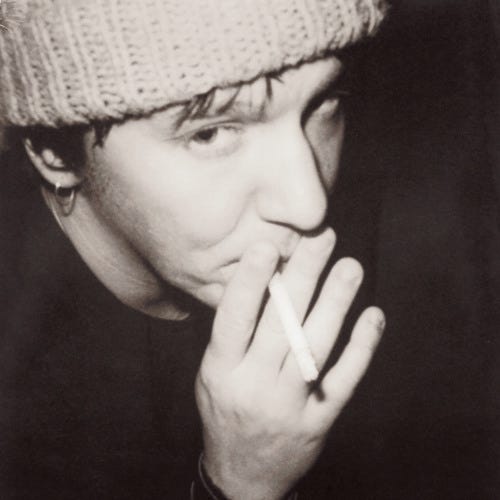

looking up from below

Elliott Smith and "Insane Optimism"

The pessimist is commonly spoken of as the man in revolt. He is not. Firstly, because it requires some cheerfulness to continue in revolt, and secondly, because pessimism appeals to the weaker side of everybody. The person who is really in revolt is the optimist, who generally lives and dies in a desperate and suicidal effort to persuade all other people how good they are.

G.K. Chesterton, A Defense of Sanity (2)

One of the wonderful things about writing for your own blog rather than for a journal or publication is that it is perfectly acceptable to cite a half-forgotten YouTube comment as the basis for your article.

I've been a fan of Elliott Smith for a long time. I'm not sure exactly when I first heard about him and that's largely due to the fact that when you grow up in Oregon and have even the foggiest interest in folk music, his legacy seems to be lurking around every corner. I remember sometime in middle school watching a YouTube upload of one of his finest songs, "Waltz #2" and reading the top comment which said something along the lines of:

"There are other musicians who are at the top looking down. They choose to make sad and depressing music, but Elliott Smith is at the bottom and he's looking up."

I've thought quite a bit about this concept over the years, and I've occasionally made a mental distinction between art/media that is "looking up" or that is "looking down", either from “below” or “above”. The kind of art that is made not to relish in misery but to work through it… That art always seems to be the finest. The music that was popular when Elliott Smith entered the musical scene, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, was grunge. This is a type of music which "looks down" if there ever was one. Don't get me wrong, there's plenty of amazing grunge music, but it is a genre which conflated sadness with coolness.

I think this rule applies to plenty of other things too. A chief example for me would be Dostoevsky. He was a man who led a dark, troubled life and his writing is accordingly dark and troubling. Yet, his tendency to have his characters descend into a kind of personal hell seems to only give him a better vantage point by which to gaze at the heavens. In The Brothers Karamazov, he dispenses a endlessly deep piece of wisdom: "in sorrow, seek happiness". This is precisely the attitude I am discussing here.

Elliott Smith's music comes from a place of pain. That much is immediately obvious. Even when you listen to him for the first time. From the first song on his first album "Roman Candle", you can immediately detect a deep sadness and anger with a chorus like, "I want to hurt him/I want to give him pain". Yet there's something about the music, not just the subject matter, but also the actual composition that feels like it has a bitter, tearful optimism. Even in a song about a very particular break-up, he wrote "Say Yes", a song he himself called, "insanely optimistic". This description is apt, as it suggests that optimism can resemble insanity in a situation which appears hopeless. Elliott Smith's music is all about looking at hopelessness and saying: if believing this will all work out makes me insane, then I'd rather not be sane.

It would be a great mistake to let the tone of Elliott Smith's music determine your perception of his character. As stated by one of his friends in the documentary Heaven Adores You,

"He would hate the idea that people know him as somebody who was always bummed. That was always a very small part of who he was."

And, indeed, in this documentary we can see Elliott's near-constant smiling in personal photographs and footage from his tours. We can also see the ways in which those close to Elliott are careful to distinguish between his narrative voices used within his songwriting efforts and his personal voice when talking about his actual, lived experience. Many who listen to his music assume its power and its repeatability lie in a kind of totalizing honesty. The kind of music critics just love to call raw.

But very few of his songs seem to assume Elliott's perspective at all, most of them are so moving because they are actually character studies. In fact, he seems to hesitate to even call them stories, referring to them instead as "just kind of little pictures made out of words." It was Elliott's ability to assume a fictional perspective and embody the emotions of a character in his lyrics with a delicate balance of specificity and universality which gave his lyrics a distinct relatability.

As is said in the documentary, "he told stories with just enough ambiguity that you could see yourself in them." That’s was Elliott’s genius. And I think the inverse is rather dangerous: to make your art purely an extension of your own life gives people the false impression that they know you personally. Sadly, this mistake was and is made with Elliott. For some reason it is far too easy to assume that his heart wrenching music was made for you alone.

It's also important to consider the context from which Elliott emerged. Seattle—and the entire PNW by extension—was becoming known for the grunge sound. Portland had its own distinct musical ecosystem during the 90s, somewhere in the realm of punk, post-punk, and grunge... Essentially, songs with loud guitars and angry vocals. This was a musical scene which Elliott's band Heatmiser was a part of. Elliott stood out from the rest of his band as being especially loud, especially angry, and exceptionally talented. This made his emergence as a whispering, acoustic-forward singer-songwriter even more surprising. His solo work puzzled the category-horny music critics who love to reduce everything into units such as "genre", "scene", and "movement". At first, critics remarked that he sounded like Simon and Garfunkel. And sure, in comparison to the relentless shouting of Portlandian-punk vocals, his wispy voice may have sounded as gentle as Paul Simon's. But to reduce his project to merely resembling 60s folk was ridiculous.

Clearly there was something new going on. His lyrics were sometimes as crass as hardcore punk but his guitar work evoked the most melancholy of folk musicians (the likes of Nick Drake and Jackson C. Franke) or the most gentle work of his grunge PNW contemporaries. But even on his debut album we can see a tremendous variety of material, from the utterly unique blend of electric and acoustic guitar in "Last Call" to "Kiwi Maddog 20/20" which sounds like it could fit neatly into Mac DeMarco's next release. Of course, his signature vocals were the main through line in this diverse array of instruments and style, which have often been described as "spider-web thin". They are uniquely haunting, with a blend of anger and sadness yet without a hint of juvenilia. His vocal delivery has been much imitated, and artists like Alex G and Sufjan Stevens can be seen as inheritors of Elliot's unique sector of folkish music.

But to return to the optimism in the work of Elliott Smith: don't let my usage of that term convince you that despite his struggles with depression he ended up just fine due to a persistent idea that "everything will work out". No. Quite the opposite. The fact is that Elliott became addicted to drugs, which led to profoundly self-destructive actions. I think there is something of a unique relationship between optimism and addiction. In my experience, addicts tend to be optimists. Or, at least, they possess a certain disposition which resembles optimism. It's the idea that despite evidence that one's addiction is a form of self-destruction, that it will nonetheless "work out". That optimism that this time will be the last time— despite the fact that that is something one cannot possibly know about the future. Or, worst of all, the optimism that you affect nobody but yourself in your self-harm.

Now, I am not suggesting that we discard optimistic attitudes, especially considering that its alternative, pessimism, will hardly do any good for a troubled person. I insist that optimism is good for you, it might be actually the best thing for you, which is why it is so dangerous. The greatest mistake an addict makes is trusting your self with yourself. In other words, we are incapable of taking care of ourselves and we cannot be trusted to be alone in a room with a substance as strong as optimism.

It is true that optimism is a type of insanity— but it is the type of insanity which threatens to drive you sane. One has to decenter the optimism that "things will work out, therefore I don't need help" with the far crazier notion that, "I need help, therefore things will work out."

Although Elliott's music may sound at first deliberately miserable. Or even nihilist. But he didn't see his music this way at all and unlike other musicians who are truly miserabilist, he didn't see the melancholic as a quality that cancels out all the others in a piece of art. I think he would likely agree with Vonnegut, insofar as he speaks of the purpose of art:

“I say in speeches that a plausible mission of artists is to make people appreciate being alive at least a little bit. I am then asked if I know of any artists who pulled that off. I reply, 'The Beatles did'.”

After all, I can't forget when I first truly appreciated Elliott— while in a moment where I thought the sadness of his album Either/Or was the only thing in the world which could match the sadness I was experiencing—I was amazed, almost offended, when I discovered that he said he was mainly trying to imitate The Beatles.

some fave songs:

You can find a playlist I made of all these songs here.

Whatever (Folk Song in C) - Elliott Smith at his most folky. It’s a favorite of mine because it shows depth in simplicity.

Between the Bars - His most well known song nowadays. It’s probably the song that has become the foundation of generations of sad folk artists. But his lyricism remains unmatched here.

Waltz #2 (XO) - The first song that showed me that he did far more than solo acoustic stuff. It perfectly demonstrates how Elliott repurposes pop instrumentation and songwriting.

Clementine - I love the way the guitar and vocal tracks seem to wrap around my brain when I listen to this with headphones.

Say Yes - A heart wrenching break up song at first glance. But the closer you look the less cliche the lyrics are. One of his catchiest too.

Independence Day - To me, this song feels incredibly chilled out. Like drinking coffee while walking down a cold, rainy street. It has beautiful backing vocals.

A Question Mark - The perfect Elliott song to show someone who isn’t into folk. The saxophone in this sounds awesome.

I Don't Think I'm Ever Gonna Figure it Out - Another simple song that puts me in that kind of melancholic happiness that is impossible to describe. The kind of song I get addicted to and listen to over and over again.

King's Crossing - Has some pretty incredible instrumentation with a heavier focus on warbly pianos, ghostly backing vocals, a plucked electric guitar, and unearthly synthesizer. Audacious.

Angeles - A beautiful and iconic Elliott song that I think of every time I go to L.A.

No Name #1 - The cascading, twangy, guitar is so beautiful. I take a big sigh of relief whenever I hear this song starting.

Condor Ave - This is the epitome of Elliott’s storytelling. It’s a simple, meaningful, tragic story. A perfect song.