Every story implies a metaphysics

a few films that show why

A man holds a piece of communion bread in one hand and a needle in another. He is about to stab it, to test whether there is any blood or presence of Christ contained in the bread. He's an egomaniacal atheist, who takes the lack of God's existence to mean permission for him to do anything. As he stabs the bread, nothing happens. He laughs maniacally, realizing he's been feeling guilt for the bad things he's been doing for no reason. He exclaims "what a joke!" He heads home.

And yet... Just a few moments later, something miraculous happens. A trail of slime leads him back to the church where he stabbed the bread. Entering the room again, the film suddenly bursts into color. The bread has been repaired! God is real, apparently, within a film that seems to mostly care about shocking its audiences. A film called The World's Greatest Sinner. It ends this way, because it knows there's nothing more suspenseful than toying with genuine metaphysical questions.

In 1962, a deranged man named Timothy Carey somehow got a camera in his hands. He was known in Hollywood as something of a maniac... He faked his own kidnapping during the shooting of Kubrick's Paths of Glory, which got him fired. If Kubrick fires you for being insane—you know that you're really something special. But he continued to get work in the film industry as a character actor. His performances exude sleaze and slime. But he had ambitions to be a director. And this resulted in his 1962 film, The World's Greatest Sinner, the only film he'd ever make. It's probably best known for having its score done by Frank Zappa, before he had even joined The Mothers of Invention.

It's a low budget shocker that's a satire on religion and politics. The film exudes the same sleaze that Carey does. It follows a man named Clarence Hilliard who changes his name to God Hilliard and begins a political party named "The Eternal Man's Party". His campaign promise is an impossible, metaphysical promise: he will provide everyone with eternal life. Humans don't have to die! We only die because of the government! In fact, we are not humans at all, we are gods!!!

It's obviously a sort of Nietzschean cartoon of a villain. It reminds a bit of the iconic Brazilian horror figure, Joe Coffin. The films Joe Coffin are in, such as At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul are another good example of gradually revealing metaphysics to enhance suspense. God clearly exists in the world of Joe Coffin, even though he's an atheist. And even though he is literally sent to Hell in the second film, he still goes to war with God. It's a curious and fascinating dynamic, demonstrating how much you can play around with metaphysics.

Every story contains a little, constructed world. While the world in its entirety might not always be revealed, there is a structure of the world implied, down to the smallest particles and out to the cosmic machinations... In other words: every story implies a metaphysics. Now, the purpose of a story is not to provide answers to questions, stories serve a much subtler and stranger purpose, but they can choose to provide an answer to any question any time they want, no matter how "big".

What are these big, metaphysical questions? Why, they're the biggest ones of all, of course: does God exist, does life have any meaning, is immortality possible, are there genuine ethical truthhoods, and so on... The story as a from can take any approach it wants to these questions. They can take hard stances or soft stances. And some of the most thrilling moments in storytelling occur when the audience gets the opportunity to "peek" behind the curtain and see how things are really working.

Perhaps this is what gets on people's nerves in regards to media that is billed as religious. When one goes to see a Christian movie, that is overtly Christian, all the mystery's been taken out of that movie's metaphysical world. I think the religious identity of a creator is one of the most interesting and telling biographical details for researchers and historians, but there's something incredibly boring about life's biggest questions being completely circumvented in a narrative. Furthermore, some really interesting things happen when people make a narrative world in spite of their own metaphysical leanings, i.e. when an atheist makes a movie that's world is theist or vice versa.

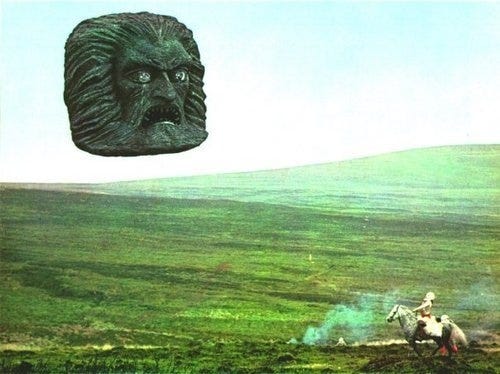

A film that plays around with its metaphysics quite a bit is Zardoz. Apparently, the director, John Boorman made this strange sci-fi film after he wasn't able to secure funding to make a full-blown adaptation of Lord of the Rings. So, instead, he decided to make his own "strange world". And strange it is. It has a civilization/barbarism dynamic in which bandits of men in weird fetishistic outfits shoot, kill, and rape anyone they lay their eyes on. Then they go to their god, ZARDOZ, and give him their loot/food. In exchange, ZARDOZ gives them guns to continue the killing. And so on. But then Connery, a leader figure of these banditos, sleeps in the big floating head (for reasons unexplained?). He accidentally kills the guy who operates the Big Head, in a sort of Wizard of Oz fashion. In fact, Connery actually discovers that that is where ZARDOZ's name comes from! (a.k.a. wiZARDofOZ)

The big head then takes him to a zone called a vortex where special people called the eternals live. They've apparently figured out immortality--don't sleep, just meditate, and don't have sex. The big head is a fake god made by the elites to collect food for themselves. Everything is figured out, the eternals can live forever. But it becomes mundane, and the excitement Connery's character represents eventually results in the return of the eternals sex drive and death drive... They want the little death (orgasm) and death itself. And that's just what happens, as they let Connery and his crew murder them all as they die in a sort of martyr's ecstasy.

The weird thing about this is that it presumes that immortality is possible, while arguing for a type of skeptical atheism. I suppose God's existence and immortality don't necessarily have to always be coupled as beliefs, but they stereotypically are. In fact, you could suggest Zardoz represents a weird trend in beliefs in our age: more people believe in heaven than God (which seems rather backwards, to me). Again, the film cannot muddle with these questions without implying a metaphysics.

The best moment I've seen in a film that deliberately asserts its metaphysics is in Lars Von Trier's Breaking the Waves. In a film that mostly feels cynical and cruel to its leading woman, there is an underlying sense that she has a noble, almost sacred, aim. Rather than spoiling the premise of the film (which is shocking) I will settle with merely spoiling the ending. After a film of everything going wrong for the protagonist, and the universe seemingly being cruel and indifferent, the final scene depicts a boat searching for the body of the protagonist. We start inside the boat--and hear a dull sound of ringing. The characters excitedly rush out to hear the origin of this sound. They find that the sounds of bells are literally coming from heaven.

It's a surreal and magical ending, which surprises its audience with its reveal of metaphysics. Compound on top of this the fact that Von Trier is himself an atheist, and it only deepens the ending's effect. Almost as a reversal of the old Wizard of Oz man-behind-the-curtain. In a metaphysical sense, the film spends much of its runtime trying to convince us that the Wizard was only a man, only to reveal at the last moment that the man was really a wizard—that this ordinary woman really was a sort of saint.

Zed (Sean Connery's character) snuck into the Zardoz head BECAUSE he discovered The Wizard of Oz. That was a flashback scene. The wizard, in fact, selected Zed to discover him, because he observed Zed's uncommon intelligence and curiosity, and thus the plot was born to disrupt the current order. In a metaphysical sense Zed then breaks into a static system and rules as a Wise King, except in this case involving sex and death.

This made me realize why I like a lot of films that have Christian elements (Signs and Prisoners for example), but find Christian media to be horrible. I think it's the lack of any actual doubt or uncertainty to be grappled with in the films' metaphysics, as if that in itself would be blasphemy, that leaves Christian films feeling saccharine and wholly detached from the actual world we live in.