Earthseed's Feedback Loop

Octavia E. Butler's Parable series toyed with systems theory and accidentally created a religion

“All human beings (and all mammals) are guided by highly abstract principles of which they are either quite unconscious, or unaware that the principle governing their perception and action is philosophic. A common misnomer for such principles is ‘feelings’”

- Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind

In the 20th century, a new intellectual movement emerged which represented a paradigm shift in how we perceive ourselves and our relationship with the natural world: systems theory. Intellectuals working in fields ranging from ecology to cybernetics have begun to refuse to settle for reductionist models, preferring to study holistic systems. From this shift in academic pursuit has emerged a prominent myth: that the world is somehow a self-correcting system… and that it does not have a trajectory, then we may give it one.

Octavia E. Butler’s Parable series was written after these fields of studies had achieved prominent cultural influence. Her novels act as a type of thought experiment: when neo-liberal capitalism eventually self-destructs, what type of religion(s) will seem attractive to us? This paper puts her theoretical religion in conversation with the concurrent developments happening in ecology and systems theory at the time. Butler’s novels offer a unique prediction of the future, where we not only see an author considering what could happen in the future based on current historical trajectories, but also, and more importantly, how will we think about these things which will happen and what solutions will be offered?

1. What is systems theory?

In Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, the book’s protagonist, Laren Oya Olamina, explains her conception of God as change. When a character Travis asks what she means by this, she says, “change is ongoing. Everything changes in some way— size, position, composition, frequency, velocity, thinking, whatever. Every living thing, every bit of matter, all the energy in the universe changes in some way. I don’t claim that everything changes in every way, but everything changes in some way”. To this explanation, Travis says, “sort of like saying God is the second law of thermodynamics” (Butler 218).

What these characters are talking about is a conceptualization of the world, nature, and humans' interaction with it as all fundamentally affecting and feeding into each other. What Olamina is attempting to formulate is her own type of holistic systems theory.

Throughout the humanities and sciences, there has been a turn from studying things to studying holistic systems, or, in art critic Jack Burnham’s words, “we are now in transition from an object-oriented [culture] to a systems-oriented culture” (Shanken 12). For instance, in sociology, there is social systems theory, in the environmental sciences, there is ecosystem ecology, and in the computer sciences, there is cybernetics. The overarching name for this interdisciplinary intersection is “Systems Theory”. These various academic advances were bleeding into the political and social life of America in time for Octavia E. Butler’s Parable series. The theory invented by the novel’s protagonist, Earthseed, is its own unique type of systems theory raised to the level of religious truth.

The story of systems theory begins in the 1930s. With biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy, who took the laws of thermodynamics outside the bounds of closed systems, instead choosing to investigate open systems, in what would later be called General Systems Theory. Tis theory of general systems is described by art historian Edwards A. Shanken as one which,

“Emphasized holism over reductionism, organism over mechanism and process over product. In contrast to traditional western scientific approaches to knowledge, it shifts attention from the absolute qualities of individual parts and addresses the organization of the whole in more relativistic terms, as a dynamic process of interaction among constituent elements” (Shanken 13).

The field of cybernetics developed alongside general systems theory, emerging from annual interdisciplinary conferences, and the two terms were used more-or-less interchangeably. At this stage, cybernetics and systems theory was primarily focused around systems which have achieved steady-states, often looking to nature, or ecosystems, as a paragon of self-sustainability. But, as identified by Shanken, this was only the first of three waves of cybernetic studies. The second wave emphasized the observer’s role in said systems, seeing them as inextricably linked to the system itself, thus, in scientific experiments, the scientist is an active participant in the experiment, emphasizing the reflexivity of interactions with systems. Finally, a third wave focused on emergence, with John Conway’s “game of life” serving as a case study of how “simple cellular automata” can generate “unexpectedly complex behavior” (Shanken 14). Yet, despite these technological innovations, increasing our ability to identify patterns and measure emergence, ecologists soon found that ecosystems are in fact quite unpredictable and unstable.

Octavia E. Butler is writing in the 1990s, after ecology and cybernetics had become well established fields, but also in the moment where the tendency to think in terms of holistic systems was waning. Her protagonist Lauren Olamina offers her own unique ecological vision, which accepts much of the systems theory thought of the past, while embracing the idea that nature is in fact unstable and ever-changing. This paper will attempt to put Olamina’s philosophy in conversation with third-wave era cybernetic and systems theory, identifying how she creates a unique vision of a holistic system in the realms of the ecological, social, and metaphysical. Lauren’s thought also importantly evolves based on her circumstances, eventually moving her community from primarily a physical space to a digital space. But before we engage with Olamina’s unique form of systems theory, we must identify the worldview which she is opposing and critiquing.

2. A Critique of a Holistic Politics of Self-Interest

Leonard Peikoff, a passionate defender and intellectual heir of Ayn Rand’s philosophy of objectivism, when responding to a critic of Rand, who claims her philosophy is not a closed system, said,

“Yes, it is. Philosophy, as Ayn Rand often observed, deals only with the kinds of issues available to men in any era; it does not change with the growth of human knowledge, since it is the base and precondition of that growth [...] Objectivism holds that every truth is an absolute, and that a proper philosophy is an integrated whole, any change in any element of which would destroy the entire system.” (Peikoff, Fact and Value).

This is a fascinating entry-point to our discussion of politics, as Peikoff believes the “closed”-ness of this philosophical system is its strength, but from Olamina’s view, it is of course a weakness. Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy assumes that if individuals act in their own self-interest, then all sorts of systems will be self-sustaining.

This is the type of politics which Octavia E. Butler is interested in responding to in her Parable series. It is a unique prediction of the far-right politics to come, largely extrapolated off trends in conservative thought during Reagan-era Neoliberalism. In the first book, Parable of the Sower, we get the first hints of this vision of far-right politics. When the main character begins to hear that a local town, Olivar, has been purchased by a company, she narrates, “something new is beginning–or perhaps something old and nasty is reviving” (Butler 118). This politics, which seems both old and new, I suggest is a type of vision of Christian nationalist as a type of holistic system.

As the book series progresses, a character named Andrew Steele Jarret gains traction as a far-right presidential candidate. In the second book, we receive a depiction of an America ruled by what Butler sees the future of far-right American politics as being. This politics is explained most succinctly in this passage,

“Jarret insists on being a throwback to some earlier, “simpler” time [...] he wants to take us all back to some magical time when everyone believed in the same God, worshiped him in the same way, and understood that their safety in the universe depended on completing the same religious rituals and stomping anyone who was different. There was never such a time in this country” (Butler 15).

This is the Christian nationalist aspect of Jarret-era politics. Butler, presciently, does not predict this form of politics will simply be a rebranding of white supremacy (although Jarret strategically never opposes such politics) but rather a type of othering of anything which does not conform to a new state church, “we must accept Jesus Christ as our savior [...] and the Church of Christian America as our church” (Butler 205). This means even an African American can take part in this far-right politics, and even gain significant power, such as Olamina’s brother does. This is not white nationalism. But it is just as dangerous.

Rather than a type of racial hierarchy, there is an understanding that everyone has their “place” in society, which is its own type of systems theory interlaced with politics. In Jarret’s vision for the world, every person, community, and nation has its place. Even if this means tolerating the violence of crusaders and the poverty of minorities alike, there is an underlying order which God has set up, and which America should follow. This politics bears a remarkable similarity to Jan Smuts’ philosophy of holism, the former prime minister of the Union of South Africa. In historian of ecology, Peder Anker’s words,

“Every human being would have its place in society, every animal would have its place in the environment [...] struggling to work toward fulfilling their wholeness in the greater whole. It is an order of nature, and an order of society which celebrates equilibrium. It is a static world. And holism became a tool to make the British Empire more stable” (All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace).

Jarret, too, is looking to stabilize the American nation, and it is this promise of stability (to make America great again*) which appeals to supporters of all sorts of backgrounds. Yet this politics of holism does not come without its modifications. There is a uniquely extreme form of individualist thought as well, the promise that if we all act in our own self-interest, then this will benefit the economy. In this way, self-interest becomes in the interest of the collective. This extreme variant of neo-liberalism can be seen as passed through Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy, depicted in books such as The Virtue of Selfishness. Olamina’s philosophy is built off the inverse of this vision, saying, “More people die of unenlightened self-interest than of any other disease” and “only in partnership can we thrive, grow, Change. Only in partnership can we live” (Butler 133). Jarret sees self-interest as a route towards national stability, while Olamina sees partnership as a route towards change.

* note that I am not injecting this term. The phrase MAGA appears in the Parable series (published in the 80s) as an uncanny prediction.

3. Ecological Vision: Change as Stability

Fundamental groundwork for laying out Olamina’s political vision which will be able to properly combat Jarret’s, involves looking at how Olamina conceptualizes nature. This is true of a systems theory approach in general. Cybernetics seems to tell us how ecosystems are able to stabilize themselves and this stability in nature is seen as an ideal model for how to construct human society. As documentarian Adam Curtis put it,

“This fusion of cybernetics and ecology was going to lead to far more than just a new idea of nature. For, out of it was about to come a new organizing principle for human society as well. It would be a vision of a new kind of world. One without the authoritarian exercise of power and the old political hierarchies, a vision that was different from past ideologies, because it mirrored how order was created in nature” (All Watched Over…).

While Olamina’s Earthseed doesn’t fully embrace the idea of harmonious nature to the extent of other real-life hippie communes which arose out of the cybernetics and systems theory movement, Earthseed still assumes that the Earth is a type of cohesive system, and we should see ourselves as part of this whole. This is representative of a move away from the Enlightenment perspective of human beings as somehow separate from nature, “If we humans are, as Lauren believes, and as I believe, a part of Earth in significant ways, then perhaps we can’t, or shouldn’t, leave and go to another world. The system of Earth is self-regulating, but not for any particular species, in the same way that the human body has its own metabolic logic” (Canavan 136).

The idea that nothing separates us from nature is captured in Olamina’s writing, “There is nothing alien / About nature. / Nature / Is all that exists. / It’s the earth / And all that’s on it [...] It's God, / Never at rest. / It’s you, / Me, / Us” (Butler 380). Nature and humanity are part of the same system of feedback loops, and how we affect nature will affect us. Part of this perspective likely permeates Butler’s own philosophy, as the setting of the Parable series is a future wrought with climate change induced catastrophe.

In Gerry Canavan’s major study of Butler’s work, he compares Olamina’s conception of nature with a famous outgrowth of the systems theory movement, the Gaia hypothesis, as formulated by chemist and environmental scientist James Lovelock, “the Gaia hypothesis suggests the idea of an Earth that seeks harmony and stability, a planet that “wants” to nurture its animal life and keep it both alive and healthy”; apparently, Butler would have used this concept subversively in her never-published third book, Parable of the Trickster, “here is Butler’s characteristically perverse turn: What if human settlers from another world landed on a world that was similarly “alive”—and fiercely devoted to repelling the foreign objects, the human astronauts, who had invaded it?” (Canavan 124). The main idea from ecology which cross-pollinates with Butler’s work, is the idea that our planet (and ironically, not others) might actually somehow help us survive, if only we work with it, rather than against it. Olamina deifies nature, and the reflexivity present in it, seeing our only salvation as one in which we work with the natural world.

By deifying nature, Olamina is engaging with a type of “deep ecology”, the theoretical point where systems theory and spirituality meet. One of the foremost systems thinkers of the deep ecology variety, Fritijof Capra, described it as such, “ecological awareness, in that deep sense, recognizes the fundamental interdependence of all phenomena and the embeddedness of individuals and societies in the cyclical processes of nature [...] ultimately, deep ecological awareness is spiritual or religious awareness” (Shanken 23). These visions of nature are, more often than not, fundamentally non-hierarchical; this plays into Olamina’s vision of intelligence in society corresponding directly to power struggles. As she describes struggles between humans in general as fundamentally negative, “All struggles / Are essentially power struggles, / And most are no more intellectual / than two rams / knocking their heads together”, while collectivity is a fundamentally positive force, “Civilization is to groups what / intelligence is / to individuals. It is a means of / combining the / intelligence of many to achieve / ongoing / group adaptation” (Butler).

Again, there is a fundamental non-hierarchical but collaborative order to human life as well as the world’s cohesive ecosystem, this is what physicist Fritijof Capra calls the “web of life”, and ascribes it a mystical (almost orientalized) quality, describing it as a fundamental truth of ancient wisdom, “the ‘web of life’ is, of course, an ancient idea, which has been used by poets, philosophers, and mystics throughout the ages to convey their sense of the interwovenness and interdependence of all phenomena” (Capra 34). The divine, in this conception, is found not above creation, but within what holds all of life together.

However, Olamina is not seeking stability, or what is called an “evolutionary steady-state” in ecological terms, but rather, change. This is a conception of ecology more in line with ecological research around the 90s and 2000s, which points us towards a very different vision of nature than the old utopian visions of ecological stability. What ecologists such as Daniel B. Botkin found when studying the histories of environments, is that our vision of the ecosystem as something which has reached an enviable state of stability was an illusion. Botkin claimed that when you reconstruct the history of an ecosystem “you saw nothing but change” (Curtis). For instance, while studying bull moose populations in Isle Royale National Park, Botkin found a chaotic history,

“in the almost half-century that I have studied nature's character, I have come to realize that the seeming constancy of the harbor symbolized a false myth about nature, while the moose that kicked at the shore—complex, changeable, hard to explain, but intriguing and appealing in its individuality—was closer to the true character of biological nature, with its complex interplays of life and physical environment on our planet” (Botkin).

It is as if Butler’s novel was directly in response to the recent paradigm shift in ecology: that the common denominator in ecosystems is not stability but change. But Olamina still sees a way to use this vision of nature to shape her own type of utopia, if nature is constantly changing, then we should change it to fit our desired trajectory, “Earthseed is thus constituted by a Darwinian recognition of the eternal flux of life as well as a post-Darwinian attempt to seize control of that flux and apply it toward human ends, first and foremost the long-term longevity of the species as such” (Canavan 128). Nature for Olamina, then, is not to be dominated in the traditional sense… yet its chaotic, unpredictable power is to be harnessed to our advantage. Nature is not cognitive, but we are.

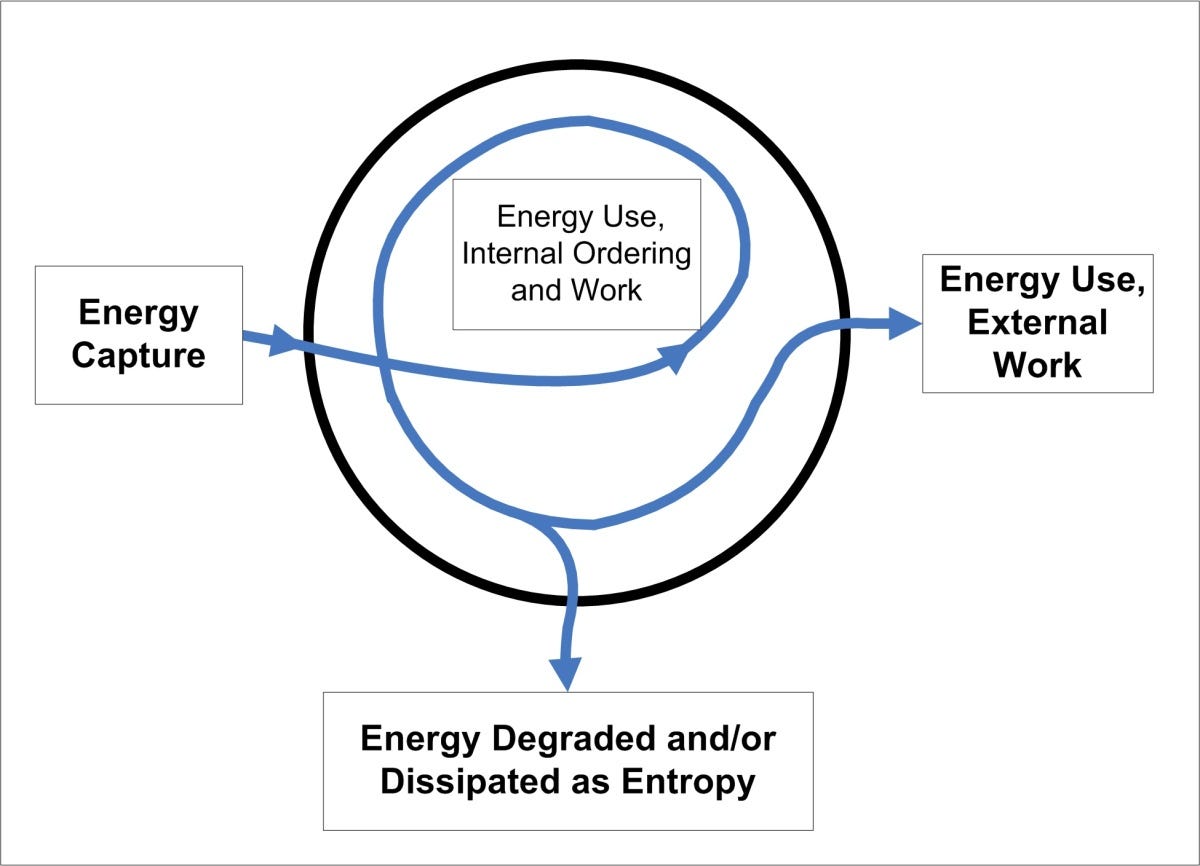

IV. Social Vision: Dissipative Structures

Olamina’s conception of social organization is a non-hierarchical “web of life”-type model. Within the philosophical and/or religious perspective of Earthseed, it does not matter whether or not this reflects the natural order, because humanity should “shape” it anyways. Olamina’s ideal type for social order is the self-organizing system which continually adapts from outside input, or in systems theory terms, a dissipative structure. The concept of dissipative structures emerges from thermodynamics, which is defined thus, “(1) that it is an open system, maintaining its pattern of organization through continuous exchange of energy and matter with its environment and (2) that it operates far from thermodynamic equilibrium” (Shanken 26). This term was brought into systems theory to understand how dynamical systems may approach some type of order without an equilibrium or “steady-state”. Olamina conceives of a similar concept in her ecological and social vision, as her daughter describes, “she saw chaos as natural and inevitable and as clay to be shaped and directed” (Butler 108). Just like the dynamical quality of nature, a group must accept constant change and diversity in order to thrive, her social model is one which is “emergent” rather than prescribed, “from one, many; / from many, one; / Forever uniting, growing, dissolving– / forever Changing. / The universe / is God’s self-portrait” (Butler 315).

In concrete terms, Olamina first conceived of her Earthseed project as a physically self-organizing system. This is Acorn, a commune which she hoped could serve as a model for other potential Earthseed communes to learn from. Olamina sees social practice as such, “partnership is giving, taking, / learning, teaching, offering the / greatest possible benefit while doing / the least possible harm. Partnership is mutualistic symbiosis. Partnership / is life”; not only is constantly bending towards symbiosis an ideal, but it is also an open system, “any entity, any process that / cannot or should not be resisted or / avoided must somehow be / partnered” (Butler 133). This is in opposition to attempts at a strictly closed system. The gated community Olamina grows up in can be seen as a microcosm of Neo-liberal ideology in its more moderate form, a place where “openness” is sacrificed for security. Jarret’s America is an attempt towards a gated community on the national scale, promising a type of political steady-state where extremists and dissidents all have their place. Olamina attempts an open system within an increasingly insecure world, seeking the social version of what ecologists call “entropy balance”. Key to maintaining a closed, secure system is a strict hierarchy, which Olamina attempts to invert. Of course, the commune does not stay truly non-hierarchical, and strong personalities emerge, most notably Olamina, who becomes known as “Shaper” in Acorn. Due to her condition of hyperempathy (a type of emotional reflexivity), she becomes aware of how she can manipulate her commune members towards her own unique vision. Regardless, this physical version of Earthseed does not last long.

After Olamina’s physical community is wiped out by Christian America Crusaders vindicated by the Jarret administration, she realizes “how easy it is to destroy such a community”, and decides she needs to make “something harder to kill”, “not only a dedicated little group of followers, not only a collection of communities as I once imagined but a movement” (Butler 295). Although only briefly discussed, Olamina harnesses recent innovations in information technology in order to evangelize her religion. This is an attempt to create an open system of religion which remains immune to predatory forces. This is a dissipative system on the national scale.

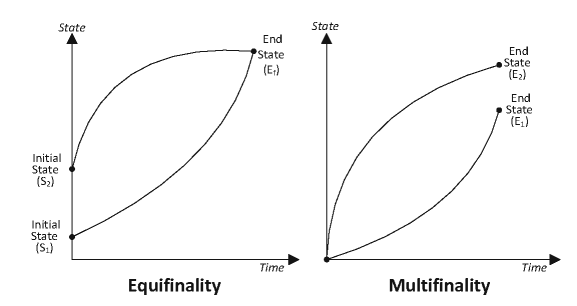

V. Conclusion: Divine Equifinality

The opening words of Parable of the Sower are “All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you” (Butler 3). This is essentially a poetic description of a feedback loop brought to the level of metaphysics, as opposed to a strict picture of linear causality, Olamina proposes looking at everything you do as feeding back into yourself. This type of bi-drectional, capital-C “Change” is “the only lasting truth”. For Olamina this is where you find God. What she means when she says we should “shape God '' is that humans play a part in creating a type of equifinality for nature itself. Equifinality is another systems theory term– referring to an end state for an open system which can be achieved through any number of means. For Olamina this is her achievable heaven: humanity’s colonization of other planets.

This is the apex of her form of systems theory as religion. Rather than engage in self-interested politics as a way to achieve a social equilibrium, Olamina involves our role within the global ecosystem as part of her political vision. The same way that ecologists and systems theorists have found that nature is seemingly unpredictable and inconsistent, Olamina recognizes the need for a cohesive worldview which sees the world as a fundamentally ever-changing system. Although nature seems to have no direction, this is the role humanity plays for Olamina, we are shapers who can conform nature to a destiny we choose. The great irony is that the destiny she chooses is that we must apparently abandon a natural world we have already altered and look forward to a different one. What Butler had in store for Olamina in her unwritten books was an ugly reality– that no other planet is truly suited for human life besides the one it emerged from.

Butler fascinatingly resists being apocalyptic. Even the selfish politics which Olamina devotes her life to extinguishing eventually passes. One of the potential versions of Parable of the Trickster contained the “incredibly dark notion” that “Olamina’s diagnosis might even be wrong: Butler imagines a [future colony] that is able to make contact with Earth, which more or less replies, It’s great to hear from you, but listen, we solved all our problems while you guys were in Hypersleep. Things are great here now; please don’t come back” (150). Butler had a pessimistic outlook on humanity– so pessimistic in fact that it seems to paradoxically bend back into a unique type of hope. She has little faith that anyone really knows how the world works, much less how it should work. This means being skeptical of those who claim they can save us– as well as those who promise an impending apocalypse.

Consider, furthermore,

Butler’s work embodies a strange truth: the world will continually get uglier and more beautiful. Abandoning it doesn’t seem to be a solution.

Special thanks to Dr. Bryan Santin who oversaw the writing of this essay.

Works Consulted

All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace. Directed by Adam Curtis, BBC, 2011.

Bateson, Gregory. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. University Of Chicago Press, 2000.

Botkin, Daniel B. “Global Warming and an Odd Bull Moose.” Wall Street Journal, 19 Dec. 2009, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704107104574573723651114320.

Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Talents. Grand Central Publishing, 2019.

Canavan, Gerry. Octavia E. Butler. S.N, 2017.

Capra, Fritjof. The Web of Life : A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. Anchor Books, 1997.

Crafford, F. S. Jan Smuts : A Biography. Kessinger Publishing, 2005.

Félix Guattari. The Three Ecologies. Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Helen Rayburn Caswell. The Parable of the Sower. Abingdon Press, 1991.

Lovelock, J. E. “Gaia as Seen through the Atmosphere.” Atmospheric Environment (1967), vol. 6, no. 8, Aug. 1972, pp. 579–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(72)90076-5.

Mehaffy, M., and A. Keating. “‘Radio Imagination’: Octavia Butler on the Poetics of Narrative Embodiment.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States, vol. 26, no. 1, Mar. 2001, pp. 45–76, https://doi.org/10.2307/3185496.

Peikoff, Leonard. “Fact and Value.” Peikoff.com, 29 Mar. 2010, peikoff.com/essays_and_articles/fact-and-value/.

Rand, Ayn, and Nathaniel Branden. Virtue of Selfishness : A New Concept of Egoism. Paw Prints, 2016.

Shanken, Edward. Systems. The Mit Press, 2015.

I love your brain ♡

This reminds me a lot of The Overstory by Richard Powers. It deals a lot with the idea of systems and the holistic interconnectedness of reality. It also explored the idea of mirroring within forests, humanity, and computers.

"note that I am not injecting this term. The phrase MAGA appears in the Parable series (published in the 80s) as an uncanny prediction." It's worth noting that Reagan used the campaign slogan "Let's Make America Great Again" and MAGA is evoking similar ideas in various ways. It's worth exploring the collaborative tone of the Reagan phrase compared to the imperative tone of the Trump phrase.